xxxxxThe English novelist and satirist Samuel Butler is best remembered today for his semi-

SAMUEL BUTLER 1835 -

Acknowledgements

Butler: self-

xxxxxThe English novelist and satirist Samuel Butler is remembered today for his semi-

xxxxxThe English novelist and satirist Samuel Butler is remembered today for his semi-

xxxxxButler was born at Langar Rectory, near Bingham in Nottinghamshire, where his father was the local vicar. He attended Shrewsbury School, where his grandfather Samuel Butler had been a distinguished headmaster before becoming Bishop of Lichfield. Given such a family background, he was clearly destined for a life in the Church, at least in the eyes of his father. He studied classics at St. John’s College, Cambridge, and graduated with first class honours in 1858. On the wishes of his father, he then worked in a poor London parish to prepare himself for the life of a clergyman, and it was at this stage that the young Butler, harbouring doubts about the virtue of Victorian Christianity, and determined to go his own way in the world, rebelled against the strict moralistic regime he had endured during his life at Langar Rectory. He made it clear that he wanted to be an artist, but this idea was met with such opposition from his father that he abandoned his home and took off to New Zealand in September 1859. There, with money advanced by his father, he eventually managed to set up a sheep farm -

xxxxxIt was soon after arriving in New Zealand that he got hold of a copy of Darwin’s Origin of Species, published in 1859, and this work -

xxxxxIt was soon after arriving in New Zealand that he got hold of a copy of Darwin’s Origin of Species, published in 1859, and this work -

xxxxxButler returned to London in August 1864, and, having increased his capital twofold during his five years in New Zealand, he was able to purchase an apartment in Clifford’s Inn, just off Fleet Street. This was to be his home for the rest of his life, and it was here, as a self-

xxxxxRecognition as a writer came in 1872 with the publication of Erewhon, a witty and bizarre satire in which he again takes up his two main themes religion and the theory of evolution. Set in a strange land beyond the mountains -

xxxxxButler’s major work, The Way of All Flesh, was written between 1873 to 1884, but it was not published until 1903. By then it was accepted as part of the on-

xxxxxButler’s major work, The Way of All Flesh, was written between 1873 to 1884, but it was not published until 1903. By then it was accepted as part of the on-

xxxxxHaving taken an early interest in the theory of evolution, Butler wrote a series of books on Darwinism throughout his writing career. These included Life and Habit (1877), Evolution, Old and New (1879), Unconscious Memory (1880), and Luck or Cunning (1887). In these he put forward sensible modifications to Darwin’s theories, particularly to those relating to what he called Darwin’s “blind process” of natural selection. And Butler also made a valuable contribution to world literature by translating into English Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Perhaps less valuable but nonetheless intriguing was his The Authoress of the Odyssey, published in 1897, in which he put forward the theory that the Odyssey was written by a young Sicilian woman, and his Shakespeare’s Sonnets Rearranged of 1899, a rearrangement which, he claimed, revealed a homosexual affair!

xxxxxHaving taken an early interest in the theory of evolution, Butler wrote a series of books on Darwinism throughout his writing career. These included Life and Habit (1877), Evolution, Old and New (1879), Unconscious Memory (1880), and Luck or Cunning (1887). In these he put forward sensible modifications to Darwin’s theories, particularly to those relating to what he called Darwin’s “blind process” of natural selection. And Butler also made a valuable contribution to world literature by translating into English Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Perhaps less valuable but nonetheless intriguing was his The Authoress of the Odyssey, published in 1897, in which he put forward the theory that the Odyssey was written by a young Sicilian woman, and his Shakespeare’s Sonnets Rearranged of 1899, a rearrangement which, he claimed, revealed a homosexual affair!

xxxxxAmong his other works were A first year in Canterbury Settlement, telling of his experiences as a frontier farmer, published n January 1863, The Fair Haven of 1873, a critical examination in which he questions the miraculous element in Christianity, and his Erewhon Revisited, a return to his strange land, published in the year before he died of consumption.

xxxxxButler met and corresponded with Charles Darwin, and his outspoken, often outrageous attacks upon “sacred cows” was much admired by the likes of Bernard Shaw, Lytton Strachey, James Joyce, E.M. Forster, and Virginia Woolf.

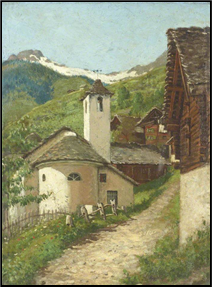

xxxxxIncidentally, on returning home from New Zealand in 1864 Butler was free to try his hand as an artist, a career his father had denied him on leaving Cambridge in 1858. He had shown some promise in drawing and watercolour painting while at Shrewsbury, and he had done some portraiture work while working in New Zealand. After studying painting at the Heatherley art school in Chiswick, his work showed some promise, and by 1876 he had had six works exhibited at the Royal Academy. His oil painting Mr. Heatherley’s Holiday is in the Tate Galley, London, and his satirical work Family Prayers is to be seen at St. John’s College, Cambridge. By the early 1870s, as we have seen, he had come to realise that he was more at home with the pen than the paintbrush, but he continued to paint during his regular walking holidays in the Swiss-

xxxxxIncidentally, on returning home from New Zealand in 1864 Butler was free to try his hand as an artist, a career his father had denied him on leaving Cambridge in 1858. He had shown some promise in drawing and watercolour painting while at Shrewsbury, and he had done some portraiture work while working in New Zealand. After studying painting at the Heatherley art school in Chiswick, his work showed some promise, and by 1876 he had had six works exhibited at the Royal Academy. His oil painting Mr. Heatherley’s Holiday is in the Tate Galley, London, and his satirical work Family Prayers is to be seen at St. John’s College, Cambridge. By the early 1870s, as we have seen, he had come to realise that he was more at home with the pen than the paintbrush, but he continued to paint during his regular walking holidays in the Swiss-

xxxxx…… Later in his life, as a Jack of all trades but close on master of none, he tried his hand at musical composition, publishing Gavottes, Fugues, Minuets and short pieces for the Piano. A great admirer of George Friedrich Handel, in 1888 he composed Narcissus, a comic cantata in the style of the German composer.

Vc-