EDMUND BURKE 1729 - 1797 (G2, G3a, G3b)

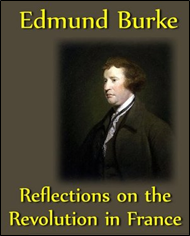

xxxxxThe orator and political writer Edmund Burke entered parliament in 1765, and quickly gained fame for his support of the American colonists in their dispute with the British government. He opposed the Stamp Act and, via his Thoughts on the Cause of Present Discontents of 1770, and two memorable speeches, he attacked the government for its unwillingness to compromise. In the 1780s he brought to public notice the mismanagement of affairs in India, and was instrumental in having Warren Hastings, a former governor-general, impeached on charges of corruption. Today he is best remembered for his Reflections on the Revolution in France, published in 1790. Conservative by nature - and later regarded as the father of conservatism - he opposed the overthrow of traditional institutions based on an hereditary aristocracy, and predicted that the social upheaval in France would lead to anarchy and a military dictatorship. Born in Dublin, he also took a close interest in Irish affairs, and was constantly calling for the lifting of the restrictions on Roman Catholics. His opposition to the king’s active role in politics helped to build up party loyalty within the House of Commons. An active member of society with a wide circle of friends, he retired in 1794 after thirty years as a Whig member of Parliament, many of them in opposition.

xxxxxThe outspoken Whig parliamentarian and political writer Edmund Burke is best remembered today for his Reflections on the Revolution in France, a work which did much to stir up opposition to the French Revolution. But in a political career spanning some thirty years, he also played a prominent and sometimes controversial part in other issues of his day, including the build up to the American War of Independence, the perennial problems associated with Ireland, and the East India Company’s mismanagement of Indian affairs. And as a political theorist he was instrumental in forming political parties at Westminster, defining the role of a member of parliament, and laying the foundations of conservatism.

xxxxxThe outspoken Whig parliamentarian and political writer Edmund Burke is best remembered today for his Reflections on the Revolution in France, a work which did much to stir up opposition to the French Revolution. But in a political career spanning some thirty years, he also played a prominent and sometimes controversial part in other issues of his day, including the build up to the American War of Independence, the perennial problems associated with Ireland, and the East India Company’s mismanagement of Indian affairs. And as a political theorist he was instrumental in forming political parties at Westminster, defining the role of a member of parliament, and laying the foundations of conservatism.

xxxxxBurke was born in Dublin and, after attending Trinity College in 1744, came to London in 1750. There he began to study law at the Middle Temple, but soon turned to a career in both writing and politics. To this early period belongs his A Vindication of Natural Society (1756), criticizing the current theory of “back to nature”, and his A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, a contribution to aesthetic theory which proved of particular interest to the French philosopher Denis Diderot, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant and the German dramatist and critic Gotthold Lessing when it was published in 1757. In the following year appeared the first volume of his Annual Register, a yearly summary of world events which he edited for close on thirty years.

xxxxxHis career in politics began in earnest when he entered the House of Commons in 1765. Here he quickly gained a reputation for his rhetorical eloquence in support of the American colonists. He strongly opposed the Stamp Act - his arguments contributing to its repeal the following year - and his pamphlet entitled Thoughts on the Cause of Present Discontents, published in 1770, was a powerful plea for a policy of understanding and conciliation towards the colonists. And this was the thrust of his two memorable speeches, On American Taxation, and Conciliation with America, delivered in the House of Commons shortly before the outbreak of fighting in 1775. In these he charged the government with intransigence, arguing that a readiness to respond to changing economic and political circumstances was necessary to avoid a collision of power and opinion. But the king and his “party” were bent on bringing the “rebels” to heel.

xxxxxHis career in politics began in earnest when he entered the House of Commons in 1765. Here he quickly gained a reputation for his rhetorical eloquence in support of the American colonists. He strongly opposed the Stamp Act - his arguments contributing to its repeal the following year - and his pamphlet entitled Thoughts on the Cause of Present Discontents, published in 1770, was a powerful plea for a policy of understanding and conciliation towards the colonists. And this was the thrust of his two memorable speeches, On American Taxation, and Conciliation with America, delivered in the House of Commons shortly before the outbreak of fighting in 1775. In these he charged the government with intransigence, arguing that a readiness to respond to changing economic and political circumstances was necessary to avoid a collision of power and opinion. But the king and his “party” were bent on bringing the “rebels” to heel.

xxxxxIn the 1780s Burke turned his attention to Indian affairs. For long concerned about the administration of the East India Company in that country, he played a leading part in condemning the company’s exploitation of the native population. The East India Bill that he drafted in 1783 called for the colony to be governed by a board of independent commissioners, based in London. When this bill was defeated, he instigated the impeachment of Warren Hastings, the former governor general of Bengal, identifying him - and unfairly so - with all that was corrupt and unjust in the administration of the colony. His opening speech for the prosecution in February 1788 lasted for four days, and the trial itself for seven years but, as we have seen, Hastings was finally acquitted on all charges. Burke’s powerful oratory certainly made public the parlous state of Indian administration and helped to hasten reform, but his speeches - as on other occasions - were emotional and abusive at times, and often marred by distortion and lack of sound judgement.

xxxxxA conservative by nature - and later regarded as the father of modern conservatism - his Reflections on the Revolution in France was published in 1790 in response to a sermon in praise of the revolution, given by the Welsh preacher Richard Price in November the previous year. Opposing what Price saw as a movement inspired by “those just ideas of civil government”, Burke came out strongly against the overthrow of traditional institutions, built up over time and based on an hereditary aristocracy. In the interests of social stability, therefore, he denounced any attempt at radical change, and his opposition increased as events in France unfolded. He saw social change as inevitable and, indeed, desirable in the course of time, but warned that sudden, speculative schemes by French “theorists” would prove unworkable and deeply damaging. They would unleash uncontrollable forces, destroy the historical process by which society had developed, and culminate in military dictatorship. The pamphlet, though somewhat overcharged in places, did much to combat the arguments of those who warmly welcomed the revolutionary movement, especially on the continent. In Britain, however, opinion did not begin to turn markedly in his favour until the execution of the French monarch in January 1793. Indeed, a number denounced his unyielding stand, including his fellow Whig, Charles James Fox, and, as we have seen, the scientist Joseph Priestley was eventually forced to emigrate to the United States because of his views.

xxxxxA conservative by nature - and later regarded as the father of modern conservatism - his Reflections on the Revolution in France was published in 1790 in response to a sermon in praise of the revolution, given by the Welsh preacher Richard Price in November the previous year. Opposing what Price saw as a movement inspired by “those just ideas of civil government”, Burke came out strongly against the overthrow of traditional institutions, built up over time and based on an hereditary aristocracy. In the interests of social stability, therefore, he denounced any attempt at radical change, and his opposition increased as events in France unfolded. He saw social change as inevitable and, indeed, desirable in the course of time, but warned that sudden, speculative schemes by French “theorists” would prove unworkable and deeply damaging. They would unleash uncontrollable forces, destroy the historical process by which society had developed, and culminate in military dictatorship. The pamphlet, though somewhat overcharged in places, did much to combat the arguments of those who warmly welcomed the revolutionary movement, especially on the continent. In Britain, however, opinion did not begin to turn markedly in his favour until the execution of the French monarch in January 1793. Indeed, a number denounced his unyielding stand, including his fellow Whig, Charles James Fox, and, as we have seen, the scientist Joseph Priestley was eventually forced to emigrate to the United States because of his views.

xxxxxAs one would expect, Burke was also active in Irish affairs, where Roman Catholics remained excluded from public office, and barred from taking part in politics. He was constantly demanding a relaxation of these restrictions and calling for economic reforms to ease the widespread poverty suffered throughout the rural areas of the island.

xxxxxHe retired from Parliament in 1794 but remained active as a writer. In 1795, for example, he began a series entitled Letters on a Regicide Peace, in which he opposed any idea of coming to terms with the French. He took an active part in society throughout his career and, as a member of the Literary Club, was acquainted, among others, with the man-of-letters Samuel Johnson, the artist Joshua Reynolds, the biographer James Boswell, and the writers Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. He was generally respected for his lively mind and gifted eloquence but, occasionally, his views were intemperate, and at times he was the object of some unkind criticism, due in the main to his humble beginnings and his Irish background.

xxxxxRegarded today as one of the greatest orators to grace the House of Commons, he also gained a reputation as a skilled parliamentarian. Opposing the king’s attempt to wield political authority via his personal friends, he sought to combat such royal patronage by building up party loyalty. And he was one of the first to attempt to define the role of a member of parliament, holding that he should attend to the local needs of his constituents, but use his own judgment on matters of national importance. He died in 1797 and was buried in the parish church of Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, the country town which was later adopted by the conservative prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, for the title of his earldom.

xxxxxIncidentally, it seems we owe the term “Fourth Estate” to Burke. According to the Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle, it was he who gave this name to the reporters’ gallery in the House of Commons, suggesting at the same time that that the press was far more important than the other three estates - the peers, bishops and commons. Given the power of the press today, his suggestion was not as fanciful as it then sounded. ……

xxxxx…… Indeed, many of his pronouncements remain valid, including: “All that is necessary for the forces of evil to win in the world is for enough good men to do nothing.”

Acknowledgements

Burke: after the Irish painter James Barry (1741-1806), 1774 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Paine: by the American portrait painter Matthew Pratt (1734-1805), 1785/95 – Collection of Historical Paintings, Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania, USA. Crabbe: by the English painter Henry William Pickersgill (1782-1875), 1818/9 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Village: date and artist unknown.

Including:

Thomas Paine

and

George Crabbe

xxxxxOne of the fiercest opponents of Burke’s denunciation of the French Revolution was the English-American radical Thomas Paine (1737-1809). Like Burke, he was an ardent supporter of the American colonists. He fought alongside them, and his pamphlet Common Sense had a huge impact, paving the way for the declaration of independence. He returned to England in 1787 and, following the publication of Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France in 1790, countered his arguments with his The Rights of Man, a work so strongly in favour of a republic that he was indicted for treason and had to take refuge in France. There he became a member of the National Convention, but narrowly escaped the guillotine for not supporting the king’s execution. It was while in France that he published his Age of Reason. This advocated the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of women, and deism, a rational belief denying divine intervention. These ideas, plus an argument against inequality in land ownership - contained in his Agrarian Justice of 1797 - lost him friends and made him enemies in America. When he returned there in 1802 he was not well received. He scraped a living in New York and died there in poverty a few years later.

xxxxxOne of the most vehement critics of Burke’s fierce denunciation of the French Revolution was the English-American left-wing propagandist Thomas Paine. He was born at Thetford, Norfolk in 1737 and after a series of jobs, emigrated to America in 1774 on the advice of Benjamin Franklin, then representing the American colonies in Britain. He worked as a journalist in Philadelphia and, like Edmund Burke, came down firmly on the side of the colonists during the events leading up to the War of American Independence. When the conflict began he fought with the colonial forces and, as we have seen, used his journalism to telling effect. His pamphlet Common Sense, blaming George III for the troubles and calling for independence, made a huge impact on the revolutionary movement and paved the way for the declaration of independence. In addition, the first copy of his sixteen stirring pamphlets entitled The American Crisis was read aloud to Washington’s troops over the winter of 1777-78 to keep up their morale during the harsh conditions at Valley Forge. The sun, he told the revolutionaries, had never shone on a cause of greater worth.

xxxxxOne of the most vehement critics of Burke’s fierce denunciation of the French Revolution was the English-American left-wing propagandist Thomas Paine. He was born at Thetford, Norfolk in 1737 and after a series of jobs, emigrated to America in 1774 on the advice of Benjamin Franklin, then representing the American colonies in Britain. He worked as a journalist in Philadelphia and, like Edmund Burke, came down firmly on the side of the colonists during the events leading up to the War of American Independence. When the conflict began he fought with the colonial forces and, as we have seen, used his journalism to telling effect. His pamphlet Common Sense, blaming George III for the troubles and calling for independence, made a huge impact on the revolutionary movement and paved the way for the declaration of independence. In addition, the first copy of his sixteen stirring pamphlets entitled The American Crisis was read aloud to Washington’s troops over the winter of 1777-78 to keep up their morale during the harsh conditions at Valley Forge. The sun, he told the revolutionaries, had never shone on a cause of greater worth.

xxxxxAmerican independence having been achieved, he returned to England in 1787, and it was then that he mixed with some of the prominent radicals of the day, including the poet and mystic William Blake, the political philosopher William Godwin, and the feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft. Two years later, when the French Revolution got under way, he found himself diametrically opposed to the statesman Edmund Burke, who, alarmed at the extent and violence of this new political upheaval, came out against it in his Reflections of 1790. In direct response, Paine wrote his The Rights of Man (1791-1792), a powerful vindication of republicanism. The hereditary monarchies of France and Britain, he claimed, were immoral constitutions. “One honest man,” he wrote, was worth more to society “than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.” This created a sensation, and such was the strength of his arguments that he was indicted for treason and, being warned by his friend Blake, only just managed to escape to France. Here he represented Calais in the National Convention and, ironically enough, narrowly escaped the guillotine for not supporting the execution of the king.

xxxxxAmerican independence having been achieved, he returned to England in 1787, and it was then that he mixed with some of the prominent radicals of the day, including the poet and mystic William Blake, the political philosopher William Godwin, and the feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft. Two years later, when the French Revolution got under way, he found himself diametrically opposed to the statesman Edmund Burke, who, alarmed at the extent and violence of this new political upheaval, came out against it in his Reflections of 1790. In direct response, Paine wrote his The Rights of Man (1791-1792), a powerful vindication of republicanism. The hereditary monarchies of France and Britain, he claimed, were immoral constitutions. “One honest man,” he wrote, was worth more to society “than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.” This created a sensation, and such was the strength of his arguments that he was indicted for treason and, being warned by his friend Blake, only just managed to escape to France. Here he represented Calais in the National Convention and, ironically enough, narrowly escaped the guillotine for not supporting the execution of the king.

xxxxxIt was while imprisoned in France during the Reign of Terror that he wrote the first part of his Age of Reason, a work advocating the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of women, and deism - a rational belief denying divine intervention. This move to what many saw as atheism, plus his attack on inequality in property ownership - contained in his pamphlet Agrarian Justice in 1797 - lost him many friends and made him enemies in America. When he returned there in 1802 he found that his immense contribution to the revolution had virtually been forgotten. He managed to scrape a living as a writer, but died in poverty seven years later.

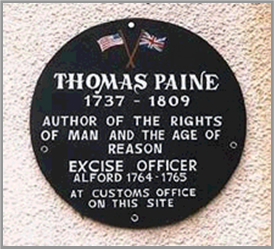

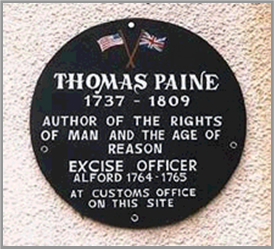

xxxxxIncidentally, Paine died in New York and was buried in New Rochelle, a farm given to him earlier in recognition of his writings during the War of American Independence. Ten years later the English political commentator William Cobbett had his remains exhumed and taken to England, planning to give Paine a funeral and a resting place worthy of his contribution to the welfare and dignity of the common man. Unfortunately his remains were lost, probably in transit, and were never recovered. The plaque illustrated here is displayed at the site of the old customs office in Alford, Lincolnshire, where Paine worked for a short time as an excise officer.

xxxxxIncidentally, Paine died in New York and was buried in New Rochelle, a farm given to him earlier in recognition of his writings during the War of American Independence. Ten years later the English political commentator William Cobbett had his remains exhumed and taken to England, planning to give Paine a funeral and a resting place worthy of his contribution to the welfare and dignity of the common man. Unfortunately his remains were lost, probably in transit, and were never recovered. The plaque illustrated here is displayed at the site of the old customs office in Alford, Lincolnshire, where Paine worked for a short time as an excise officer.

xxxxxThe Englishman George Crabbe (1754-1832) owed his fame as a poet to Edmund Burke. He saw the merit of his work and helped him to publish his manuscripts. His narrative poems, noted for their harsh, realistic portrayal of English village life, included The Village, The Parish Register, The Borough and Tales of the Hall. His work was admired by the romantic poets Robert Southey and William Wordsworth. Crabbe entered the ministry in 1781 and was vicar of Trowbridge, Wiltshire, for 18 years.

xxxxxThe Englishman George Crabbe (1754-1832) owes his fame as a poet to Edmund Burke, to whom he appealed for assistance in 1781. Burke saw the merit of his work and helped him to publish his manuscripts. His narrative poems are notable above all for their harsh, realistic portrayal of English village life, and include The Village and The Newspaper, produced in the early 1780s, and a number of works written in later life, such as The Parish Register of 1807, The Borough of 1810, and Tales of the Hall, composed in 1819. His work was much admired by the romantic poets Robert Southey and William Wordsworth, both of whom he met in 1814.

xxxxxThe Englishman George Crabbe (1754-1832) owes his fame as a poet to Edmund Burke, to whom he appealed for assistance in 1781. Burke saw the merit of his work and helped him to publish his manuscripts. His narrative poems are notable above all for their harsh, realistic portrayal of English village life, and include The Village and The Newspaper, produced in the early 1780s, and a number of works written in later life, such as The Parish Register of 1807, The Borough of 1810, and Tales of the Hall, composed in 1819. His work was much admired by the romantic poets Robert Southey and William Wordsworth, both of whom he met in 1814.

xxxxxHis most successful work, The Village, provided a stark, detailed picture of the poverty and misery of rural life, and was written to counteract the somewhat idyllic picture of village life depicted by the poet Oliver Goldsmith in his The Deserted Village of 1770.

xxxxxHis most successful work, The Village, provided a stark, detailed picture of the poverty and misery of rural life, and was written to counteract the somewhat idyllic picture of village life depicted by the poet Oliver Goldsmith in his The Deserted Village of 1770.

xxxxxCrabbe was born at Aldeburgh, Suffolk, and was apprenticed to a surgeon before leaving for London in 1780 to attempt a literary career. The following year Burke not only assisted him in having his poems published, but also helped him to enter the ministry. He became rector of Aldeburgh later that year. For the last eighteen years of his life he was vicar of Trowbridge in Wiltshire.

xxxxxIncidentally, the English novelist Jane Austen described him as her favourite poet, and in 1945 the English composer Benjamin Britten based his opera Peter Grimes on one of the grim tales that make up The Borough.

G3b-1783-1802-G3b-1783-1802-G3b-1783-1802-G3b-1783-1802-G3b-1783-1802-G3b

xxxxxThe outspoken Whig parliamentarian and political writer Edmund Burke is best remembered today for his Reflections on the Revolution in France, a work which did much to stir up opposition to the French Revolution. But in a political career spanning some thirty years, he also played a prominent and sometimes controversial part in other issues of his day, including the build up to the American War of Independence, the perennial problems associated with Ireland, and the East India Company’s mismanagement of Indian affairs. And as a political theorist he was instrumental in forming political parties at Westminster, defining the role of a member of parliament, and laying the foundations of conservatism.

xxxxxThe outspoken Whig parliamentarian and political writer Edmund Burke is best remembered today for his Reflections on the Revolution in France, a work which did much to stir up opposition to the French Revolution. But in a political career spanning some thirty years, he also played a prominent and sometimes controversial part in other issues of his day, including the build up to the American War of Independence, the perennial problems associated with Ireland, and the East India Company’s mismanagement of Indian affairs. And as a political theorist he was instrumental in forming political parties at Westminster, defining the role of a member of parliament, and laying the foundations of conservatism.  xxxxxHis career in politics began in earnest when he entered the House of Commons in 1765. Here he quickly gained a reputation for his rhetorical eloquence in support of the American colonists. He strongly opposed the Stamp Act -

xxxxxHis career in politics began in earnest when he entered the House of Commons in 1765. Here he quickly gained a reputation for his rhetorical eloquence in support of the American colonists. He strongly opposed the Stamp Act -

xxxxxA conservative by nature -

xxxxxA conservative by nature -

xxxxxOne of the most vehement critics of Burke’s fierce denunciation of the French Revolution was the English-

xxxxxOne of the most vehement critics of Burke’s fierce denunciation of the French Revolution was the English- xxxxxAmerican independence having been achieved, he returned to England in 1787, and it was then that he mixed with some of the prominent radicals of the day, including the poet and mystic William Blake, the political philosopher William Godwin, and the feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft. Two years later, when the French Revolution got under way, he found himself diametrically opposed to the statesman Edmund Burke, who, alarmed at the extent and violence of this new political upheaval, came out against it in his Reflections of 1790. In direct response, Paine wrote his The Rights of Man (1791-

xxxxxAmerican independence having been achieved, he returned to England in 1787, and it was then that he mixed with some of the prominent radicals of the day, including the poet and mystic William Blake, the political philosopher William Godwin, and the feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft. Two years later, when the French Revolution got under way, he found himself diametrically opposed to the statesman Edmund Burke, who, alarmed at the extent and violence of this new political upheaval, came out against it in his Reflections of 1790. In direct response, Paine wrote his The Rights of Man (1791- xxxxxIncidentally, Paine died in New York and was buried in New Rochelle, a farm given to him earlier in recognition of his writings during the War of American Independence. Ten years later the English political commentator William Cobbett had his remains exhumed and taken to England, planning to give Paine a funeral and a resting place worthy of his contribution to the welfare and dignity of the common man. Unfortunately his remains were lost, probably in transit, and were never recovered. The plaque illustrated here is displayed at the site of the old customs office in Alford, Lincolnshire, where Paine worked for a short time as an excise officer.

xxxxxIncidentally, Paine died in New York and was buried in New Rochelle, a farm given to him earlier in recognition of his writings during the War of American Independence. Ten years later the English political commentator William Cobbett had his remains exhumed and taken to England, planning to give Paine a funeral and a resting place worthy of his contribution to the welfare and dignity of the common man. Unfortunately his remains were lost, probably in transit, and were never recovered. The plaque illustrated here is displayed at the site of the old customs office in Alford, Lincolnshire, where Paine worked for a short time as an excise officer. xxxxxThe Englishman George Crabbe (1754-

xxxxxThe Englishman George Crabbe (1754- xxxxxHis most successful work, The Village, provided a stark, detailed picture of the poverty and misery of rural life, and was written to counteract the somewhat idyllic picture of village life depicted by the poet Oliver Goldsmith in his The Deserted Village of 1770.

xxxxxHis most successful work, The Village, provided a stark, detailed picture of the poverty and misery of rural life, and was written to counteract the somewhat idyllic picture of village life depicted by the poet Oliver Goldsmith in his The Deserted Village of 1770.