WILLIAM BOOTH 1829 -

Acknowledgements

Booth: date and

artist unknown. Preaching: date and

artist unknown. Cartoon: date and artist

unknown. Catherine: detail, photographer

unknown, contained in Catherine Booth: A Sketch

by Brigadier Mildred Duff (c1862-

xxxxxThe Englishman William Booth, the founder of the

Salvation Army and its first “general”, was born in Nottingham.

His family fell on hard times in 1842, and he had to leave school

at the age of 13. He was apprenticed to a local pawnbroker, but at

the age of 15 became convinced that his future lay in preaching

the gospel and helping the poor. With this in mind he went to

London in 1849. He lodged and worked in a pawnbroker’s shop in

Walworth in order to send money home to his family, but he spent

his spare time preaching out on the streets and on Kennington

Common -

xxxxxThe Englishman William Booth, the founder of the

Salvation Army and its first “general”, was born in Nottingham.

His family fell on hard times in 1842, and he had to leave school

at the age of 13. He was apprenticed to a local pawnbroker, but at

the age of 15 became convinced that his future lay in preaching

the gospel and helping the poor. With this in mind he went to

London in 1849. He lodged and worked in a pawnbroker’s shop in

Walworth in order to send money home to his family, but he spent

his spare time preaching out on the streets and on Kennington

Common -

xxxxxOn returning

to London he became an independent evangelist and took to the

streets. But along with his preaching of the gospel went a feeling

of deep compassion for the plight of the city’s poor, the long

hours they worked, the squalor in which they lived, and the

pitiful existence of the deprived children. He saw his role as

fighting injustice and “freeing the captured and oppressed,

sharing food and home, clothing the naked and carrying out family

responsibilities”. It was in 1865, while preaching outside the

Blind Beggar’s Pub in the East End that his extraordinary ardour

as a speaker -

xxxxxOn returning

to London he became an independent evangelist and took to the

streets. But along with his preaching of the gospel went a feeling

of deep compassion for the plight of the city’s poor, the long

hours they worked, the squalor in which they lived, and the

pitiful existence of the deprived children. He saw his role as

fighting injustice and “freeing the captured and oppressed,

sharing food and home, clothing the naked and carrying out family

responsibilities”. It was in 1865, while preaching outside the

Blind Beggar’s Pub in the East End that his extraordinary ardour

as a speaker -

xxxxxThexMission was the first step towards the foundation of The Salvation Army. This was formed in 1878 and was a stroke of genius on Booth’s part, proving without doubt that there is something of value in a name. He first thought of changing the Christian Mission to the “Volunteer Army”, but some of his followers objected to the term, arguing that they were “regular” members. Furthermore, it clashed with the then title of what is now the “Territorial Army”. As a result, in a moment of inspiration, he came up with the words “Salvation Army”. This changed the image of the organisation, widened its appeal, and put it on the road to international success. The idea of a body of Christian soldiers, marching as to war and modelled on the rank structure and discipline of the British Army, caught the public imagination amid the jingoistic atmosphere of Victorian England.

xxxxxHowever, support did not come overnight. For a number

of years opposition to this idea came from a number of sources,

including the Anglican Church. Furthermore, because this new

militant force supported the Temperance Society it became a target

for gangs of men who called themselves the “Skeleton Army” and

took as their emblem the skull and cross bones. They disrupted and

broke up meetings and, because of the violence they

xxxxxHowever, support did not come overnight. For a number

of years opposition to this idea came from a number of sources,

including the Anglican Church. Furthermore, because this new

militant force supported the Temperance Society it became a target

for gangs of men who called themselves the “Skeleton Army” and

took as their emblem the skull and cross bones. They disrupted and

broke up meetings and, because of the violence they  used,

many Salvationists were fined or imprisoned for disturbing the

peace. But this opposition gradually subsided as the Army’s good

work among the poor of London came to be appreciated. Indeed,

thousands flooded to Booth’s banner and marched behind the

movement’s military-

used,

many Salvationists were fined or imprisoned for disturbing the

peace. But this opposition gradually subsided as the Army’s good

work among the poor of London came to be appreciated. Indeed,

thousands flooded to Booth’s banner and marched behind the

movement’s military-

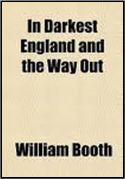

xxxxxBooth travelled the world in support of his growing

movement, but he also found time to put on paper a social welfare

scheme that went far beyond “soup and salvation”. His major work,

In Darkest England, published in 1890,

was a telling indictment of Victorian society, revealing as it did

the “cesspit of squalor, starvation and vice” which lay hidden

beneath the outward signs of progress, opulence and well-

xxxxxBooth travelled the world in support of his growing

movement, but he also found time to put on paper a social welfare

scheme that went far beyond “soup and salvation”. His major work,

In Darkest England, published in 1890,

was a telling indictment of Victorian society, revealing as it did

the “cesspit of squalor, starvation and vice” which lay hidden

beneath the outward signs of progress, opulence and well-

xxxxxBy the 1890s the street corner preacher who had been pelted with stones and shouted abuse was a man with celebrity status, respected and honoured the world over. He received the freedom of London, gained an honorary degree from Oxford University, opened a session of the U.S. Senate with a prayer in 1898, and was officially invited to the coronation of Edward VII. When he died in 1912, no less than 150,000 people filed past his coffin while lying in state, 40,000 people attended his funeral service at the Olympic Exhibition Hall, and 10,000 “soldiers” and 40 bands followed his coffin to his final resting place in Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington.

xxxxxHe made his final speech in the Royal Albert Hall. A particular passage is well worth quoting, because it sums up the man:

xxxxxWhile women

weep, as they do now, I’ll fight; while little children go hungry,

as they do now, I’ll fight; while men go to prison, in and out, in

and out, as they do now, I’ll fight; while there is a drunkard

left, while there is a poor lost girl on the streets, while there

remains one dark soul without the light of God, I’ll fight -

xxxxxHe died thee months later.

xxxxxUntilxher death in 1890

Booth was immensely helped and inspired by his devoted wife Catherine, whom he married

in 1855. A remarkable and deeply religious woman, she became a

public preacher herself in 1860, and gained a reputation as an

inspiring speaker and an outstanding social worker. Indeed,

without her support, strength and determination there may not have

been a Salvation Army. They had eight children and they also

played a part in the movement. Their eldest son, William Bramwell,

took over the movement on his father’s death; their second son,

Ballington, became commander of the Army in Australia and later

the United States; and their daughter Evangeline was the Army’s

fourth general in the 1930s.

xxxxxUntilxher death in 1890

Booth was immensely helped and inspired by his devoted wife Catherine, whom he married

in 1855. A remarkable and deeply religious woman, she became a

public preacher herself in 1860, and gained a reputation as an

inspiring speaker and an outstanding social worker. Indeed,

without her support, strength and determination there may not have

been a Salvation Army. They had eight children and they also

played a part in the movement. Their eldest son, William Bramwell,

took over the movement on his father’s death; their second son,

Ballington, became commander of the Army in Australia and later

the United States; and their daughter Evangeline was the Army’s

fourth general in the 1930s.

xxxxxIncidentally, it so happened that the words of the well known

hymn Onward Christian Soldiers first

appeared in The Church Times in 1865,

the year Booth established his Christian Mission. Written by the

eccentric Reverend Sabine Baring-

xxxxx…… During his travelling across the world Booth stayed for a while in Palestine. It is said that when visiting the Garden of Gethsemane in Jerusalem he knelt down to kiss a leper’s hand. The story might be well be apocryphal, but it is in keeping with the man. ……

xxxxx…… WhenxBooth was working in

the East End there was a company making matches called Bryant and May. A substance

used in the manufacture, a yellow phosphorus, was highly toxic and

the fumes it gave off caused sickness and sometimes death amongst

the women workers. When the company refused to substitute this

substance for a harmless version -

Including:

Thomas Barnardo

Vb-

xxxxxThe fiery

English evangelist William Booth came to London in 1849 to preach

the gospel in the streets of East London. He became a full-

xxxxxA young

evangelist named Thomas John Barnardo (1845-

xxxxxAmong those who gave support to William Booth during

his early days as a preacher was a young man named Thomas

John Barnardo (1845-

xxxxxAmong those who gave support to William Booth during

his early days as a preacher was a young man named Thomas

John Barnardo (1845- in

China and devoted his life to the care of needy children in what

Booth called “Darkest England”. By the time of his death he had

raised sufficient funds to establish close on a hundred “Dr.

Barnardo Homes” for the care and training of destitute children,

placed 4,000 in foster care, and sent 18,000 to start fresh lives

in Canada and Australia. It is estimated that in these various

ways he “rescued” no fewer than 60,000 children during his life

time.

in

China and devoted his life to the care of needy children in what

Booth called “Darkest England”. By the time of his death he had

raised sufficient funds to establish close on a hundred “Dr.

Barnardo Homes” for the care and training of destitute children,

placed 4,000 in foster care, and sent 18,000 to start fresh lives

in Canada and Australia. It is estimated that in these various

ways he “rescued” no fewer than 60,000 children during his life

time.

xxxxxA

resourceful, determined young man, he developed various ways to

make money -

xxxxxThe main aim of these homes was to feed, clothe and

educate, and to provide basic training in domestic and industrial

skills. However, throughout their time in care emphasis was placed

on religious instruction, and the welfare programme extended to

specialised centres, such as rescue homes for girls in danger, a

hospital for the very sick, homes for children with physical and

learning difficulties, and a convalescent home by the sea. The

width and diversity of these undertakings was almost bound to

involve criticism of one kind or another. At various times

Barnardo was accused of “kidnapping”, cruelty and financial

malpractice, but arbitration cleared him of all the major charges.

xxxxxThe main aim of these homes was to feed, clothe and

educate, and to provide basic training in domestic and industrial

skills. However, throughout their time in care emphasis was placed

on religious instruction, and the welfare programme extended to

specialised centres, such as rescue homes for girls in danger, a

hospital for the very sick, homes for children with physical and

learning difficulties, and a convalescent home by the sea. The

width and diversity of these undertakings was almost bound to

involve criticism of one kind or another. At various times

Barnardo was accused of “kidnapping”, cruelty and financial

malpractice, but arbitration cleared him of all the major charges.

xxxxxHe married Syrie Elmslie in 1873, and she was an immense help and comfort to him. They had seven children but three did not survive infancy. When Barnardo suddenly died of a heart attack in 1905, his funeral brought much of London to a standstill, so large were the crowds that lined the streets to pay him homage. After resting for four days at the People’s Mission Church at Edinburgh Castle (the former pub), his body was taken to Barkingside, Essex, and buried in the grounds of The Village Home.

xxxxxIncidentally, it was in the early seventies that an 11-

xxxxx…… On the way to its resting place Barnardo’s coffin was taken on the London Underground for part of the journey. The only other coffin to be transported on the Tube was that of the British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone when on its way to a state funeral at Westminster Abbey. …..

xxxxx…… At his death the charity was in debt to the tune of £249,000, but this was met by a national memorial fund, and the organization was then put on a firm financial footing. ……

xxxxx…… It would seem that Barnardo’s magnificent work for deprived children might never have been. According to one account, when he was two years old he was declared dead from diphtheria, and it was only when the undertaker was putting his body into the coffin that he detected a trace of life! …...

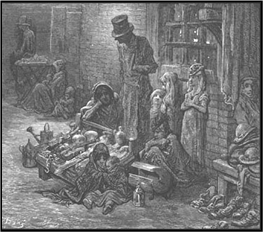

xxxxx…… Thexwidespread poverty in London at this time was

highlighted in 1872 by the publication of London:

A Pilgrimage, a book of 160 engravings

produced by the brilliant French illustrator Gustave

Doré (1832-

xxxxx…… Thexwidespread poverty in London at this time was

highlighted in 1872 by the publication of London:

A Pilgrimage, a book of 160 engravings

produced by the brilliant French illustrator Gustave

Doré (1832-

xxxxx…… Andxit was later, in 1886,

that a successful English businessman named Charles

Booth (1840-

xxxxx…… Itxwas

in these closing years of the 19th century that the American

religious leader Mary Baker Eddy (1821-

xxxxx…… Itxwas

in these closing years of the 19th century that the American

religious leader Mary Baker Eddy (1821-