JOHANN ELERT BODE 1747 -

(G2, G3a, G3b, G3c, G4)

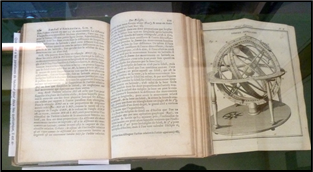

xxxxxThe German astronomer Johann Elert Bode did much to popularise the science of astronomy. His Uranographia in particular, published in 1801 and made up of 20 maps, was the first to show all the stars visible to the naked eye. He also wrote a number of popular books on astronomy, and was responsible for the production of the German nautical almanac, producing over 50 yearly volumes. However, he is best remembered today for Bode’s Law, published in 1772. This was a geometric progression which attempted to explain the relative mean distances between the Sun and its planets. It worked well when applied to the planets then known, but later, with the discovery of Neptune and Pluto, the validity of the law was called into question. It was first put forward by the German astronomer Johann Daniel Titius in 1766, so it is sometimes known as the Titius-

Including:

Jérôme Lalande

and Giuseppe Piazzi

xxxxxThe astronomer and mathematician Johann Elert Bode played a significant part in introducing astronomy to a wider public. In particular, his star atlas Uranographia, published in 1801, was a remarkable piece of work, showing for the first time all the stars visible to the naked eye. It was made up of 20 maps, and described the positions of more than 17,000 stars and nebulae, including many of the recent discoveries made by the German-

xxxxxThe astronomer and mathematician Johann Elert Bode played a significant part in introducing astronomy to a wider public. In particular, his star atlas Uranographia, published in 1801, was a remarkable piece of work, showing for the first time all the stars visible to the naked eye. It was made up of 20 maps, and described the positions of more than 17,000 stars and nebulae, including many of the recent discoveries made by the German-

xxxxxBode was born in Hamburg, Germany. As a young man he virtually taught himself the science of astronomy, and then put his knowledge to good effect in 1772 when he joined the staff at the observatory of the Berlin Academy, helping to compile the Astronomisches Jahrbuch, the German nautical almanac. He eventually became fully responsible for this publication, compiling and issuing over 50 yearly volumes. He was later appointed director of the Berlin observatory (illustrated below) and became a member of the Berlin Academy. During his career, he wrote a number of books on popular astronomy.

xxxxxToday, Bode is probably best known for Bode’s Law, a geometric progression which attempted to explain the relative mean distances between the Sun and its planets. It worked out fairly accurately in determining the distances of the six planets then known, and it did appear to assist in the discovery of a number of asteroids situated between Mars and Jupiter. However, the subsequent discovery of Neptune in 1846 and Pluto in 1930, both of which were at variance with the law, has since cast doubt on its credibility. Indeed, it is now generally considered that the relationship arrived at earlier was simply a coincidence.

xxxxxIncidentally, Bode’s Law was actually put forward in 1766 by the astronomer Johann Daniel Titius (1729-

Xxxxx…… And it was Bode who gave the name Uranus to Herschel's new planet. When the English astronomer discovered it in 1781, he named it Georgium Sidus (the Star of George) in honour of the British king George III, whilst a number of French astronomers referred to it as Herschel. But then Bode came along and called it Uranus (after Saturn’s mythological father) and, eventually, that was the name by which it came to be known.

Xxxxx…… And it was Bode who gave the name Uranus to Herschel's new planet. When the English astronomer discovered it in 1781, he named it Georgium Sidus (the Star of George) in honour of the British king George III, whilst a number of French astronomers referred to it as Herschel. But then Bode came along and called it Uranus (after Saturn’s mythological father) and, eventually, that was the name by which it came to be known.

Acknowledgements

Bode: portrait by the Prussian artist Franz Kruger (1797-

G3b-

xxxxxIt was also in 1801 that the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande (1732-

xxxxxThe year 1801 also saw the publication of French Celestial History, a comprehensive star catalogue by the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande (1732-

xxxxxThe year 1801 also saw the publication of French Celestial History, a comprehensive star catalogue by the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande (1732-

xxxxxLalande was born in Bourg-

xxxxxThen, at the age of 30, he was appointed professor of astronomy at the Collège de France, Paris, a post he held for 46 years. It was here that he published his Treatise on Astronomy in 1764, a work providing the most accurate tables of the planetary positions then available. And it was also at this time that, having observed the two transits of Venus which had occurred within the space of eight years (1761 and 1769) -

xxxxxThen, at the age of 30, he was appointed professor of astronomy at the Collège de France, Paris, a post he held for 46 years. It was here that he published his Treatise on Astronomy in 1764, a work providing the most accurate tables of the planetary positions then available. And it was also at this time that, having observed the two transits of Venus which had occurred within the space of eight years (1761 and 1769) -

xxxxxDuring his career he produced a number of popular works on navigation and travel as well as astronomy. His final work of importance was his Astronomical Biography, published in 1803.

xxxxxIt was also in 1801 that the Italian monk and astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi (1746-

xxxxxIt was also in 1801 that the Italian monk and astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi (1746-