xxxxxIn 1704, a French army combined with a Bavarian force and marched towards Vienna, but they were intercepted by the British, commanded by the Duke of Marlborough, and the Austrians, led by Prince Eugene of Savoy. The French, having fortified a village called Blenheim, stretched their army along a ridge some 3 miles long. Eugene advanced on the enemy’s left flank while Marlborough launched a direct attack upon Blenheim. This proved unsuccessful, but in order to strengthen their hold on the village the French then withdrew men from the centre of their line. Marlborough seized his chance and, leading a massive force of infantry and cavalry across a stretch of marshland, smashed through the centre of the weakened French line, and then overran the village. The French retreated in disorder. Meanwhile Eugene had broken through the east flank and put the Bavarians to flight. For the French it was their first major defeat for some 50 years, and it proved a psychological setback from which they never really recovered. For the Allies, it saved Vienna, virtually knocked Bavaria out of the war, and provided a vital boost to their confidence.

THE BATTLE OF BLENHEIM 1704 (AN)

THE WAR OF THE SPANISH SUCCESSION

Including:

The Duke of Marlborough

xxxxxIn the opening phase of the War of the Spanish Succession, the French -

xxxxxIn the opening phase of the War of the Spanish Succession, the French -

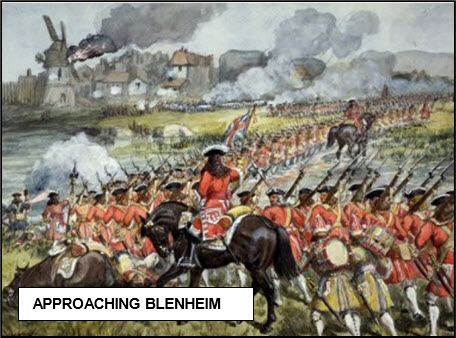

xxxxxThe French, having been forewarned of the enemy's approach, fortified the village and extended their line along a ridge some three miles long, and fronted by an area of marshy ground on either side of a small stream called Nebelbach. In order to gain some element of surprise, the Allies advanced overnight and attacked about noon the following day. Eugene advanced on the enemy's left flank, held by the Bavarians, and Marlborough made a direct assault upon Blenheim itself. This proved unsuccessful, but it had the effect of drawing enemy infantry away from the centre of the French line in order to strengthen the defences of the village. This gave Marlborough the opportunity he had planned for. He then led a massive force of cavalry and infantry across the Nebelbach and its surrounding marshland -

xxxxxThe French, having been forewarned of the enemy's approach, fortified the village and extended their line along a ridge some three miles long, and fronted by an area of marshy ground on either side of a small stream called Nebelbach. In order to gain some element of surprise, the Allies advanced overnight and attacked about noon the following day. Eugene advanced on the enemy's left flank, held by the Bavarians, and Marlborough made a direct assault upon Blenheim itself. This proved unsuccessful, but it had the effect of drawing enemy infantry away from the centre of the French line in order to strengthen the defences of the village. This gave Marlborough the opportunity he had planned for. He then led a massive force of cavalry and infantry across the Nebelbach and its surrounding marshland -

xxxxxThe Allies suffered about 12,000 casualties, killed and wounded, the French and Bavarians possibly twice that number. Among the 13,000 or so men captured was the French commander himself, Marshal Camille, Count de Tallart. The Battle of Blenheim can be seen as a turning point. Although the war had only just begun in earnest, and had eight more years to run, this was the first major defeat suffered by the French army in over fifty years, and, as such, it was a serious, psychological setback from which they never really recovered. For the Allies, it saved the city of Vienna, instilled the alliance with a great deal of confidence, and virtually knocked Bavaria out of the war. For John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, it was his most famous victory, and a grateful nation gave him a small gift -

xxxxxIncidentally, in August 1704 members of the government approached the English essayist and poet Joseph Addison and asked him to write a poem to celebrate the great victory of Blenheim. Later that year he published The Campaign, a poem addressed to Marlborough and praising his military genius. It was an immediate success, and launched Addison on his literary and political career.

xxxxxJohn Churchill, Duke of Marlborough (1650-

xxxxxJohn Churchill, Duke of Marlborough (1650-

xxxxxJohn Churchill, Duke of Marlborough (1650-

xxxxxIn the early 1690s, however, he lost favour at court -

xxxxxAs commander in chief of the English and Dutch armies during the War of the Spanish Succession, he won a series of brilliant victories over the French, particularly at the battles of Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenaarde and Malplaquet. He was created 1st Duke of Marlborough in 1702, had honours heaped upon him, and was provided with a vast stately home in Oxfordshire -

xxxxxAs commander in chief of the English and Dutch armies during the War of the Spanish Succession, he won a series of brilliant victories over the French, particularly at the battles of Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenaarde and Malplaquet. He was created 1st Duke of Marlborough in 1702, had honours heaped upon him, and was provided with a vast stately home in Oxfordshire -

xxxxxIn 1711, however, all this changed, and he found himself once more out of royal favour following his wife's quarrel with the Queen. He was falsely accused of embezzling public funds, stripped of all his public offices, and removed as commander in chief of the nation's army. The Anglo-

xxxxxMarlborough was an ambitious man, and this doubtless distorted his concept of loyalty at times, but he was an outstanding tactician on the battlefield, making highly effective use of mobility and firepower, and bringing maximum force to bear where penetration was the most likely to succeed. And he was, too, an astute diplomat, creating and then managing to maintain a broad alliance of nations in a period of conflicting political interests. He remains today one of the greatest figures in British history.

xxxxxMarlborough was an ambitious man, and this doubtless distorted his concept of loyalty at times, but he was an outstanding tactician on the battlefield, making highly effective use of mobility and firepower, and bringing maximum force to bear where penetration was the most likely to succeed. And he was, too, an astute diplomat, creating and then managing to maintain a broad alliance of nations in a period of conflicting political interests. He remains today one of the greatest figures in British history.

xxxxxIncidentally, a brilliant biography of the 1st Duke, Marlborough, His Life and Times, was written by his ancestor Sir Winston Churchill, British prime minister during the Second World War. ...…

xxxxx...... The Duke of Marlborough provided the name for one of the two principal varieties of the English toy spaniel. The King Charles spaniel -

xxxxx...... The Duke of Marlborough provided the name for one of the two principal varieties of the English toy spaniel. The King Charles spaniel -

Acknowledgements

Marlborough: detail, by the Dutch painter Adriaen van de Werff (1659-

AN-