THE BATTLE OF THE LITTLE BIGHORN, JUNE 1876 (Vb)

Including:

Colonel George Custer

Acknowledgements

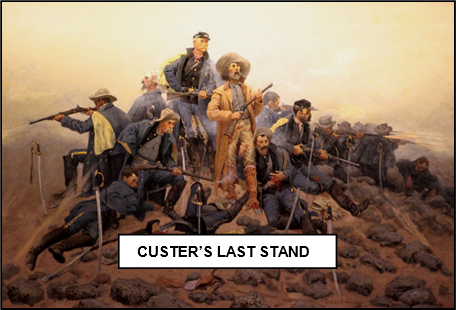

Custer: detail, May 1865, photographer unknown – Library of Congress, Washington. Battle Plan: from exploring off the beatenpath.com/Battlefields/LittleBighorn. Last Stand: by the American painter Frederic Remington (1861-

xxxxxCuster’sxfamous “last stand” took place on the 25th June 1876 at the Battle of The Little Bighorn in Montana. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (1839-

xxxxxCuster’sxfamous “last stand” took place on the 25th June 1876 at the Battle of The Little Bighorn in Montana. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (1839-

xxxxxIt was in late 1875 that the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians gathered in Montana to fight for their sacred land. The Black Hills in South Dakota had been granted to them in perpetuity by the U.S. government in 1868, but the discovery of gold in French Creek in 1874 brought an enormous flood of prospectors and miners into the area. Inxresponse, the government reneged on the agreement -

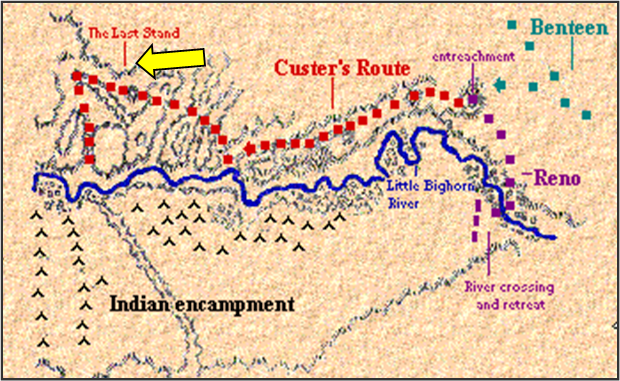

xxxxxTo force the Indians back to their reservations, the U.S. Army sent out three columns and these converged on the region in June 1876. Colonel Custer, in charge of the Seventh Cavalry Regiment, was under the command of General Alfred Howe Terry. In a plan to encircle the Indian encampment - located a force of Sioux, and Custer discarded the plan. Though unaware of the strength of the enemy -

located a force of Sioux, and Custer discarded the plan. Though unaware of the strength of the enemy -

xxxxxReno’s battalion, about 175 strong, was ordered to attack the southern end of the large Indian encampment, but heavily outnumbered he was very soon suffering heavy casualties. As a consequence, Reno was forced to retreat in disorder to woodland along the river bank, and then cross the river to gain the relative safety of high ground. Here he came under further attack but, fortunately for him and his men, he was soon joined by Captain Benteen and his three companies, returning from a futile reconnaissance mission. This combined force, strengthened by the arrival of the pack train, managed to dig in and hold their ground until the main force under General Terry reached their position on the 27th.

xxxxxMeanwhile Custer had crossed further up the river and launched an attack upon the Indian encampment from the north. Like Reno, however, he found himself confronted with swarms of warriors. Outnumbered by about 10 to 1, and fighting hand- reinforcement. He had lost contact with General Terry and his own flanks; Colonel John Gibbon’s slow moving infantry brigades were still two days or more away; and, though he didn’t know it, the third column, commanded by General George Crook, had been turned back at Rosebud Creek by an Indian attack just a few days earlier.

reinforcement. He had lost contact with General Terry and his own flanks; Colonel John Gibbon’s slow moving infantry brigades were still two days or more away; and, though he didn’t know it, the third column, commanded by General George Crook, had been turned back at Rosebud Creek by an Indian attack just a few days earlier.

xxxxxCuster and his men took what cover they could in a hollow formed in the high ground, but they were unable to use direct fire from this position and came under attack from showers of well-

xxxxxIndianxaccounts of the Battle of The Little Bighorn confirm the bravery shown by the men of Custer’s last stand, but in the post-

xxxxxAs regards Custer himself, there was severe criticism of his conduct in some quarters. His decision to attack the Indian encampment in the first place, when he was not aware of the strength of his enemy, and his decision to divide his force of 655 men into three detachments -

xxxxxIncidentally, as far as the U.S. military is concerned there was in fact one survivor from the Battle of Little Bighorn, a horse named Comanche. Owned by Lieutenant Colonel Myles Keough, he recovered from his wounds and lived for another seventeen years. During this time he toured the country with the 7th Cavalry, taking part in parades and patriotic events. On these occasions he wore a saddle but never had a rider. When he died he was preserved and put on display at the University of Kansas, where he can be seen to this day, (detail illustrated). ……

xxxxx…… The battlefield was established as a national cemetery in 1879, and as the Custer Battlefield National Monument in 1946. In 1991 it was renamed the Little Bighorn Battle National Memorial so as to include the Native Americans who died during the battle. To them, Little Bighorn is remembered as the Battle of Greasy Grass.

xxxxxAt his “sun dance” ceremony, held a month before the Battle of The Little Bighorn, Chief Sitting Bull had accurately predicted a stunning victory over the “blue coats”, but, ironically enough, this battle also proved to be the “last stand” for the American Indians themselves. Enraged by this defeat - Many Sioux, including women and children were killed, and the Black Hills, the centre of the dispute, were placed outside the reservations and declared open to white settlement. And later that summer General Terry trapped some 3,000 Sioux in the Tongue River valley and forced all but a few back into their reservations. Crazy Horse finally surrendered to General Crook in May 1877 and was killed in a scuffle some four months later. Chief Sitting Bull, having spent four years in Canada, returned and gave himself up at Fort Buford, North Dakota, in 1881. He rejoined his tribe two years later.

Many Sioux, including women and children were killed, and the Black Hills, the centre of the dispute, were placed outside the reservations and declared open to white settlement. And later that summer General Terry trapped some 3,000 Sioux in the Tongue River valley and forced all but a few back into their reservations. Crazy Horse finally surrendered to General Crook in May 1877 and was killed in a scuffle some four months later. Chief Sitting Bull, having spent four years in Canada, returned and gave himself up at Fort Buford, North Dakota, in 1881. He rejoined his tribe two years later.

xxxxxAs we shall see, the final end to Sioux resistance came in 1890 (Vc) with their defeat at the notorious Battle of Wounded Knee. This marked the end of 350 years of Indian Wars.

xxxxxIncidentally, in 1885 Sitting Bull spent some months on tour with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, earning $50 a week for his appearance, and a dollar or more for every picture he autographed! He was killed in the run-

Vb-

xxxxxCuster’s famous “last stand” took place in June 1876. The Sioux and other tribes had come out of their reservations in 1875 to protest against the horde of miners and prospectors entering the Black Hills, land which was sacred to them and had been granted to them by the government. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (1839-