LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1770 -

(G3a, G3b, G3c, G4)

xxxxxThe great German composer Ludwig van Beethoven gained fame with his nine symphonies, but he wrote masterpieces across the whole range of musical composition, producing five piano concertos, two violin concertos, 17 string quartets, 32 piano sonatas, an opera, Fidelio, and a number of concert overtures. His most productive period was from 1803 to 1812, during which he composed his two powerful symphonies, the Third (his Eroica of 1804) and Fifth, together with his Pastoral (the Sixth), a serene hymn to the beauty of nature. Best known among his sonatas are his Moonlight and Appassionata. His monumental work, the Ninth Choral Symphony, came later in 1824, and was his greatest success. The onset of deafness as early as 1798 deeply distressed him, and he showed great courage in overcoming this disability. He based his work on the classical style of Mozart and his teacher Haydn, but the emotional content of his compositions ushered in the Romantic period, evoking a sense of freedom and romantic imagery. An independent composer and a republican at heart, he was the first to marshal the power of music in the service of the people, writing for the rights and dignity of the individual. “What is in my heart,” he said, “must come out and so I write it down”. He gained a European reputation, and numbered among his friends and acquaintances the composers Rossini, Schubert and Liszt, and the German writers Goethe, Hoffmann and the Grimm Brothers. His work influenced, in particular, the composers Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Wagner, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler.

xxxxxLudwig van Beethoven, one of the greatest composers of all time, was born in Bonn. A member of a family of musicians, he showed remarkable keyboard skill from an early age. He gave his first piano recital in May 1778, and was the assistant organist at the court of the Elector of Cologne at Bonn before he was twelve years old. He made his first visit to Vienna in February 1787, and it was then that he met Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, then at the height of his fame. The Austrian composer was much impressed with his playing, predicted that “the world shall speak of this youth”, and agreed to have him as a pupil. Unfortunately in July of that year Beethoven received news that his mother was dying and he had to return to Bonn. With her death and his father’s incapacity through drink, he was obliged to support his two younger brothers for a number of years. By the time he returned to Vienna in 1792, Mozart was dead, and it was then that he was invited to study under the Austrian composer Joseph Haydn. He was never to return to the city of his birth, occupied that year by the armies of the French Revolution.

xxxxxLudwig van Beethoven, one of the greatest composers of all time, was born in Bonn. A member of a family of musicians, he showed remarkable keyboard skill from an early age. He gave his first piano recital in May 1778, and was the assistant organist at the court of the Elector of Cologne at Bonn before he was twelve years old. He made his first visit to Vienna in February 1787, and it was then that he met Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, then at the height of his fame. The Austrian composer was much impressed with his playing, predicted that “the world shall speak of this youth”, and agreed to have him as a pupil. Unfortunately in July of that year Beethoven received news that his mother was dying and he had to return to Bonn. With her death and his father’s incapacity through drink, he was obliged to support his two younger brothers for a number of years. By the time he returned to Vienna in 1792, Mozart was dead, and it was then that he was invited to study under the Austrian composer Joseph Haydn. He was never to return to the city of his birth, occupied that year by the armies of the French Revolution.

xxxxxBeethoven quickly settled down in Vienna and his brothers joined him a few years latter. Because of the fighting then sweeping across central Europe he did little travelling. Apart from his summer holidays, the occasional concert nearby, and short tours to Prague, Dresden and Berlin, he remained in the city for the rest of his life. He got on fairly well with Haydn, but found his tuition inadequate and, unbeknown to him, had extra lessons with a number of other teachers. Wishing to be independent, he sought no official musical appointment, but he made quite a comfortable living by giving piano lessons, selling his compositions through local publishers, and giving concerts. In his early years in Vienna he conducted his own orchestral works, and often played his own piano pieces, astonishing his audiences with his brilliant improvisation and the vitality of his playing. He also made a large number of friends -

xxxxxGiven his association with and admiration for both Mozart and Haydn, it is not surprising that much of his music was based on the Viennese high classical style -

xxxxxGiven his association with and admiration for both Mozart and Haydn, it is not surprising that much of his music was based on the Viennese high classical style -

xxxxxNowhere was this more so than in his “heroic decade”, that middle period from 1803 to 1812 during which he produced some of his finest work. Therein, much of his music had a sense of destiny, but it was not all confined to the heroic. It expressed a whole range of emotions, from the passionate to the tender. It began with his powerful Third Symphony, the Eroica, completed in 1804, and included his Fifth Symphony, another dramatic, vigorous work of heroic passions, and his Waldstein and Appassionate sonatas. Among other masterpieces of this period were his three Razumovsky Quartets, his Fourth Symphony, his Violin Concerto, the Coriolanus Overture, and the incidental music for Goethe's drama Egmont. And outstanding within his works of serene melody was his Sixth Symphony, the Pastoral, a hymn to the countryside, created from a deep love of nature, and regarded today as one of his loveliest compositions.

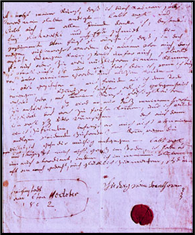

xxxxxBut if these years 1803 to 1812 marked the pinnacle of his fame, they also began his years of personal isolation, the result of his increasing deafness. The onset of this impairment, starting around 1798, was a bitter blow to him and at one stage he contemplated suicide. In 1802, while staying at a house in the village of Heiligenstadt, just outside Vienna, he wrote a letter to his brothers -

xxxxxBut if these years 1803 to 1812 marked the pinnacle of his fame, they also began his years of personal isolation, the result of his increasing deafness. The onset of this impairment, starting around 1798, was a bitter blow to him and at one stage he contemplated suicide. In 1802, while staying at a house in the village of Heiligenstadt, just outside Vienna, he wrote a letter to his brothers -

xxxxxAnd these years also brought disappointment in love. He was not, it must be said, an over attractive man. He was small in stature, cared little about his appearance, and lacked the social graces, but women found his musical genius attractive. As a result, he had a number of unfulfilled love affairs. In 1803, for example, he lost his “dear sweet girl” Giulietta Guicciardi, one of his pupils, to whom he dedicated his haunting Moonlight Sonata. She left him to marry a count. In 1806 he became engaged to Marie-

xxxxxAnd these years also brought disappointment in love. He was not, it must be said, an over attractive man. He was small in stature, cared little about his appearance, and lacked the social graces, but women found his musical genius attractive. As a result, he had a number of unfulfilled love affairs. In 1803, for example, he lost his “dear sweet girl” Giulietta Guicciardi, one of his pupils, to whom he dedicated his haunting Moonlight Sonata. She left him to marry a count. In 1806 he became engaged to Marie-

xxxxxGiven these disappointments in love, and his withdrawal from general society due to his deafness, it is not surprising that in the last period of his life his compositions lost some of their dramatic appeal and became much more intense and inward looking. However, they were none the worse for that. Indeed, to these years belong his technically demanding Hammerklavier Sonata, his Missa Solemnis, and his monumental Ninth Symphony, composed, on and off, over 30 years. This unique symphony, part choral, was a triumph at its premier in 1824, a fact which, we are told, was not appreciated by Beethoven himself until one of the singers turned him to face the audience! Today its concluding chorus, Ode to Joy by the German poet and dramatist Friedrich von Schiller, serves as the official anthem of the European Union.

xxxxxHis brother Caspar Carl died in 1815 and this was the start of a five-

xxxxxBeethoven’s works spanned the whole range of musical endeavour, and few men of music have matched the grandeur of his imagination and the power of his expression. Apart from his nine symphonies, his works included his opera Fidelio in 1805 (a tale of tyranny and oppression which was revised and well received in 1814), five piano concertos (including the Emperor of 1809) and two violin concertos (one unfinished), 17 string quartets, his Mass in D, (finished in 1823) and a number of concert overtures, including Leonora and Coriolanus. Of his 32 piano sonatas, his Moonlight of 1801 and his Appassionata of 1805 are perhaps his best known. And to this must be added 5 sonatas for cello and piano, 10 for violin and piano, and sets of piano variations. Most popular among his “Bagatelles” (short piano pieces) is Für Elise (For Elise), a work expressing love and affection that was composed in 1810, but not discovered and published until 1867.

xxxxxNo composer has made more of an impact upon the world of music than Beethoven, and none has changed that world to a greater degree. His compositions were not produced to order, the whim of an aristocratic patron, but were the outpourings of his own intense, personal feelings. In his hands music became an artistic intention -

xxxxxBeethoven numbered among his friends and acquaintances the talent of his day. They included his teacher Haydn, of course (whose funeral he attended in 1809), the composers Rossini, Schubert, Weber and Liszt, and the German writers Goethe, Hoffmann and the Grimm Brothers. And his work, as one would expect, had a profound influence on future composers. His Seventh Symphony clearly coloured works by Mendelssohn, Berlioz and Wagner, and his Ninth Symphony had a telling effect upon Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler. When coming to terms with his deafness at the beginning of the century he wrote to a friend, "If only I were rid of my affliction I would embrace the whole world." He never did rid himself of his affliction, but he embraced the whole world nonetheless.

xxxxxIncidentally, Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, was originally dedicated to Napoleon, a man he greatly admired, but when he heard that he had assumed the title of emperor and was, as he put it, “like all other men”, he scratched out Napoleon’s name on the dedication and scrawled over the top “Heroic Symphony to Celebrate the Memory of a Great Man”. And his Fifth Symphony also played a part in history. It became particularly well-

xxxxxIncidentally, Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, was originally dedicated to Napoleon, a man he greatly admired, but when he heard that he had assumed the title of emperor and was, as he put it, “like all other men”, he scratched out Napoleon’s name on the dedication and scrawled over the top “Heroic Symphony to Celebrate the Memory of a Great Man”. And his Fifth Symphony also played a part in history. It became particularly well-

xxxxx…… In May 1809, when the French bombarded Vienna, Beethoven was obliged to take refuge in the basement of his quarters (with cotton wool stuffed in his ears and a pillow over his head!), but it was a different story five years later when the Congress of Vienna was held following Napoleon’s defeat. At a splendid reception and concert at the Rasoumowsky Palace, he was introduced to the crowned heads and leading aristocracy of Europe, and received warm tributes from them for a programme which included his cantata The Glorious Moment and his Seventh Symphony. ……

xxxxx…… Throughout his life Beethoven jotted down musical ideas and compositions on scraps of paper or in notebooks, often when out walking in the countryside. Some 7,000 pages of these jottings (or “autographs”) have survived and they provide a fascinating insight into how -

xxxxx…… Beethoven’sxPiano Sonata in C Major, known as the “Waldstein”, was composed in 1804 and dedicated to his friend and benefactor Count Waldstein (1762-

xxxxx…… One particular incident which marred the friendship between Beethoven and Goethe occurred one day when they were out walking in the park at the centre of the Bohemian town of Teplitz. On coming face to face with the Empress, Goethe gave a deep bow, but Beethoven markedly ignored her. This “Incident in Teplitz”, as it came to be called, deeply offended Goethe, and the two men never met again.

xxxxxBeethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, owed something to the Italian-

xxxxxBeethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, owed something to the Italian-

Acknowledgements

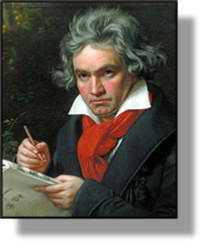

Beethoven: by the German painter Josph Karl Stieler (1781-

Including:

Luigi Cherubini

G3c-