THE FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS

1792 -

THE TREATIES OF BASLE 1795

xxxxxThe Reign of Terror came to an end with the fall of Robespierre in July 1794, but the period that followed -

Including:

The Battle of Fleurus

and The Directory

xxxxxThe fall of Robespierre in July 1794 put an end to a ten month orgy of organized blood letting. The Convention, once more in the hands of the moderate bourgeoisie, returned to some semblance of moderation and legality. The Paris Commune, that stronghold of radicalism, was dissolved, the guillotine was dismantled, the militant Jacobin club was closed down, and the Revolutionary Tribunal was disbanded.

xxxxxButxthe removal of these outward symbols of bloody repression in no way solved the problems of the hour. The period that followed on from the Reign of Terror -

xxxxxAnd it was this same republican army that turned the tide on the battlefield. As we have seen, it was the military strategist Lazare Carnot, a member of the Committee of Public Safety, who, more than anyone else, had been the architect of this new military machine. Working as from August of 1793, he had raised the first national conscript army, a vast enlistment of some 800,000 men, made up into 14 well-

xxxxxAs we have seen, as early as October 1793 the French general Jean Baptiste Jourdan had defeated the Austrians at Wattignies-

xxxxxAs we have seen, as early as October 1793 the French general Jean Baptiste Jourdan had defeated the Austrians at Wattignies-

xxxxxSuch was the success of the French armies, that by the spring of 1795 a number of France’s opponents were prepared to come to terms. This string of agreements, sometimes known as the Treaties of Basle, began in April when Prussia, at loggerheads with Austria over the size of its share in the final Partition of Poland, turned neutral. France responded by making peace with a number of German states, including Saxony, Mainz and the Bavarian Palatinate. Holland, which, by then had been overrun and turned into a republic, made a settlement the same month by which it was obliged to accept its status as a virtual French satellite. Then in May, Sweden agreed to withdraw its opposition, and in July Spain, ceding her part of the West Indian island of San Domingo, abandoned the coalition and settled for peace.

xxxxxThese agreements enabled the Convention to complete its work in drawing up a new form of government, the “Constitution of the Year III” (as the republican calendar would have it). The Directory, as the executive power was called, was in the hands of five men, elected for a term of five years by a legislature composed of a lower house called the Council of Five Hundred, and a Senate of 250 called the Council of Ancients. These two bodies were to be elected on a limited franchise, and, by special decree, two thirds of the new parliament was to be drawn from the Convention, thereby preventing a slide back to terror or monarchy.

xxxxxThis liberal settlement was approved by plebiscite and put into effect in November, but not before an attempt was made to strangle it at birth. The provision whereby the republican ideals of the Convention would be perpetuated, brought violent opposition. Moderates and royalists alike took up arms against what they saw as a blatant infringement of electoral liberty. In the first week of October (13th Vendémiaire An IV) a vast multitude, put by some as 26,000 strong, assembled from all parts of the city and prepared to march on the National Convention. Fortunately for the government, a young officer by the name of General Napoleon Bonaparte happened to be in town at this time. Having already distinguished himself by his recapture of Toulon in 1793, he was assigned the task of putting down the insurrection. This he promptly achieved by what he later described as “a whiff of grapeshot”. Having hurriedly brought up some artillery overnight, he ordered the firing of one brief cannonade as the columns of insurgents approached the government chambers via the Rue St. Honoré. Stopped in their tracks, the vast crowd broke up in disorder and fled, leaving hundreds of their comrades dead or dying in the street (illustrated).

xxxxxThis liberal settlement was approved by plebiscite and put into effect in November, but not before an attempt was made to strangle it at birth. The provision whereby the republican ideals of the Convention would be perpetuated, brought violent opposition. Moderates and royalists alike took up arms against what they saw as a blatant infringement of electoral liberty. In the first week of October (13th Vendémiaire An IV) a vast multitude, put by some as 26,000 strong, assembled from all parts of the city and prepared to march on the National Convention. Fortunately for the government, a young officer by the name of General Napoleon Bonaparte happened to be in town at this time. Having already distinguished himself by his recapture of Toulon in 1793, he was assigned the task of putting down the insurrection. This he promptly achieved by what he later described as “a whiff of grapeshot”. Having hurriedly brought up some artillery overnight, he ordered the firing of one brief cannonade as the columns of insurgents approached the government chambers via the Rue St. Honoré. Stopped in their tracks, the vast crowd broke up in disorder and fled, leaving hundreds of their comrades dead or dying in the street (illustrated).

xxxxxOnce secure, the Directory now felt able to turn its attention to those countries which still threatened the new order in France. It conceded that the island state of Britain was, for the present at least, beyond direct action, but not so Austria and Sardinia. Under plans drawn up by Carnot, a member of the Directory, two armies were prepared for a direct assault on Germany, and put under the command of Generals Jourdan and Morau. The young General Bonaparte (illustrated), in recognition of his timely defeat of the October resurrection, was appointed commander of a third, subsidiary army, designed to attack the Austrian territories in northern Italy and the kingdom of Piedmont-

xxxxxOnce secure, the Directory now felt able to turn its attention to those countries which still threatened the new order in France. It conceded that the island state of Britain was, for the present at least, beyond direct action, but not so Austria and Sardinia. Under plans drawn up by Carnot, a member of the Directory, two armies were prepared for a direct assault on Germany, and put under the command of Generals Jourdan and Morau. The young General Bonaparte (illustrated), in recognition of his timely defeat of the October resurrection, was appointed commander of a third, subsidiary army, designed to attack the Austrian territories in northern Italy and the kingdom of Piedmont-

Acknowledgements

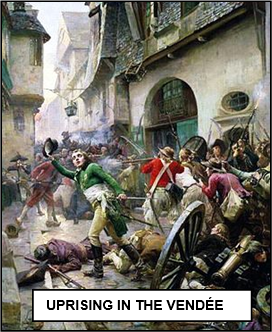

Vendée: by the French painter Paul-

G3b-