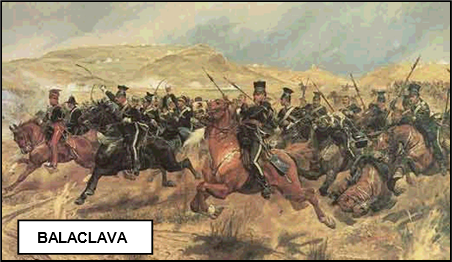

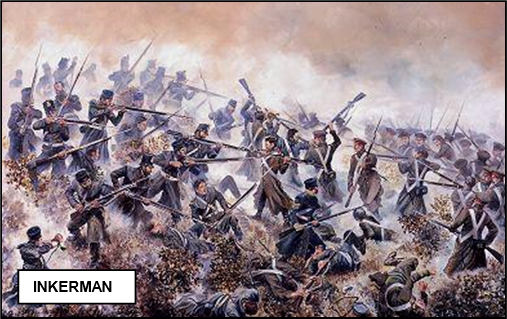

xxxxxAs we have seen, Turkey, fearing Russian designs on the Black Sea, declared war on Russia in 1853. Britain and France followed suit in March 1854 and landed an army on the Crimean peninsula in the September. They intended to attack and capture the naval base of Sevastopol, but their way was barred by a Russian force north of the city. In the Battle of Alma River which followed, the allies eventually defeated the Russians, but they did not push on at once to take the naval base. When they reached there it was well defended, and they were forced to lay siege to the city for nearly a year. In the meantime, the Russians, anxious to raise the siege, attacked the British lines at the Battle of Balaclava. They were repelled by the Heavy Brigade in the South Valley and forced to retreat, but then, due to a command error, the Light Brigade was ordered to attack the Russian guns at the head of the North Valley. In the infamous “Charge of the Light Brigade” that followed, the British cavalry lost 272 men, killed or wounded. The situation was saved by a French cavalry charge, and the intervention of British infantry. In November at the Battle of Inkerman, the Russians again attacked the British in order to relieve Sevastopol. They took the British lines, but were later forced to retreat. By now, however, the Russian winter had set in and, as we shall see, the allies were to suffer even greater hardship in 1855. This was the year in which Sevastopol was finally taken and nurse Florence Nightingale became famous for her work in caring for the sick and wounded.

THE CRIMEAN WAR 1853 -

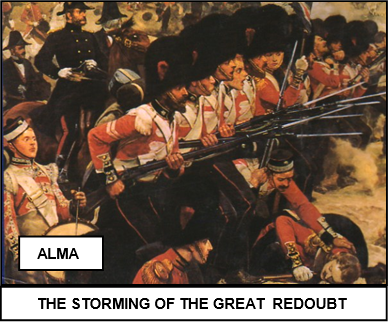

THE BATTLES OF ALMA RIVER, BALACLAVA AND INKERMAN 1854 (Va)

Acknowledgements

Map (Crimea): licensed under Creative Commons – https://britlitwiki.wikispares.com. Alma: by the English painter and illustrator Richard Caton Woodville (1856-

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in October 1853 that war broke out between Turkey and Russia, caused in the main by the ambitions of Tsar Nicholas in the Balkans and Black Sea areas. The Turks were confident that both Britain and France would come to their support and this they did in March 1854. Both countries had already sent naval forces to the Black Sea, but the war was primarily a military one. The British army, under the command of Lord Raglan, numbered around 28,000, the French force, led by Marshal Saint Arnaud, was slightly larger. The Austrian government remained neutral but, despite the help it had received from Russia in quelling a revolt in Hungary in 1849, it strongly opposed the Russian advance into the Balkans and was prepared, therefore, to use its neutrality to good effect. This it did. Its threat to enter the war on the side of the Turks forced the Russians to evacuate both Moldavia and Walachia -

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in October 1853 that war broke out between Turkey and Russia, caused in the main by the ambitions of Tsar Nicholas in the Balkans and Black Sea areas. The Turks were confident that both Britain and France would come to their support and this they did in March 1854. Both countries had already sent naval forces to the Black Sea, but the war was primarily a military one. The British army, under the command of Lord Raglan, numbered around 28,000, the French force, led by Marshal Saint Arnaud, was slightly larger. The Austrian government remained neutral but, despite the help it had received from Russia in quelling a revolt in Hungary in 1849, it strongly opposed the Russian advance into the Balkans and was prepared, therefore, to use its neutrality to good effect. This it did. Its threat to enter the war on the side of the Turks forced the Russians to evacuate both Moldavia and Walachia -

xxxxxThe Russian evacuation of the Danubian Principalities meant that the allies were obliged to rethink their theatre of operation. Eventually they decided to land on the Crimean peninsula and capture Sevastopol, headquarters of Russia’s Black Sea fleet on the south-

xxxxxThe allied victory at Alma River opened the way to the naval base at Sevastopol, but this battle had already shown some of the signs of weakness in logistics and command which was to hamper the allied campaign throughout the war. Because of the lack of transport, much equipment, including tents and clothing, had to be left at Eupatoria, the port of embarkation, whilst in the battle itself, confused orders almost ended in disaster for the British during their frontal attack. Furthermore, because of disagreements between the impetuous Lord Raglan and the more cautious Saint Arnaud, the allied forces failed to pursue the Russians from the battlefield and capture Sevastopol with comparative ease. As a result, by the time the allies reached the city, its defences had been strengthened and they were obliged to lay a siege. This lasted close on a year, during which time the besieging forces were subject to a number of costly attacks.

xxxxxThe allied victory at Alma River opened the way to the naval base at Sevastopol, but this battle had already shown some of the signs of weakness in logistics and command which was to hamper the allied campaign throughout the war. Because of the lack of transport, much equipment, including tents and clothing, had to be left at Eupatoria, the port of embarkation, whilst in the battle itself, confused orders almost ended in disaster for the British during their frontal attack. Furthermore, because of disagreements between the impetuous Lord Raglan and the more cautious Saint Arnaud, the allied forces failed to pursue the Russians from the battlefield and capture Sevastopol with comparative ease. As a result, by the time the allies reached the city, its defences had been strengthened and they were obliged to lay a siege. This lasted close on a year, during which time the besieging forces were subject to a number of costly attacks.

xxxxxIncidentally, the Scottish surgeon James Thomson (1823-

xxxxxThe second major confrontation of the war came the following month, October, when the Russians, attempting to relieve Sevastopol, launched an attack upon the rear of the British positions at the port of Balaclava, six miles south- abandoned by the Turks in their earlier engagement.

abandoned by the Turks in their earlier engagement.

xxxxxToxput a stop to this, the British Commander, Lord Raglan (1788-

xxxxxIncidentally, the Battle of Balaclava inspired the Charge of the Light Brigade, the famous poem composed by the English poet Lord Tennyson and published in 1854. Two verses are quoted below:

“Forward, the Light Brigade!”

Was there a man dismayed?

Not though the soldier knew

xxSomeone had blundered:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

xxRode the six hundred. ……

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them

Cannon behind them,

xxVolleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell

They that had fought so well;

Came through the jaws of Hell,

All that was left of them,

xxLeft of six hundred.

xxxxx…… The Earl of Cardigan, the man who led the charge, was one of the lucky survivors. On his return he was feted as a hero, but he was later obliged to refute allegations that he had fled from the field. Ironically, he died in 1868 after falling from Ronald, the handsome chestnut that had taken him through Tennyson’s “Valley of Death”. A knitted jacket that the Earl reputedly wore during the Crimean campaign came to be known as a “cardigan”.

xxxxxThere followed, in November, the Battle of Inkerman, a seven-

xxxxxThere followed, in November, the Battle of Inkerman, a seven-

xxxxxThe Battle of Inkerman marked the onset of the dreadful Crimean winter. In 1855, as we shall see, this brought even greater hardship, death and disease to the poorly fed and badly clothed army which continued to lay siege to Sevastopol until the September. And it was on the very day that the Battle of Inkerman was fought that the English nurse Florence Nightingale arrived to take charge of the nursing in the barrack hospital at Scutari, near Constantinople, an event which was to introduce new standards in the care of the sick and wounded.

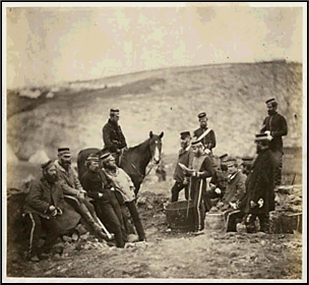

xxxxxIncidentally, the print on the right is by the English photographer Roger Fenton (1819-

xxxxx…… The Illustrated London News also published engravings of drawings of the Crimean War produced by the French artist-

Va-