xxxxxThe Londoner Francis Bacon was a learned man -

FRANCIS BACON 1561 -

1st Baron Verulam and Viscount St Albans

Acknowledgement

Bacon: detail, portrait by the English painter John Vanderbank (1694-

xxxxxFrancis Bacon was a lawyer, essayist, statesman and philosopher, as well as a pioneer in scientific method. He was born in London, studied law at Trinity College, Cambridge, and became a Member of Parliament in 1584. Although a nephew of Lord Burleigh, he associated with his uncle's rival, the Earl of Essex, but turned against him when he led a revolt against Queen Elizabeth, and in 1601 helped to secure his conviction as a traitor. He defended this action in his Apology of 1604, in which he argued that his first loyalty was to his sovereign. He then went on to enjoy a successful legal career, ending up as Lord Chancellor in 1618. Three years later, however, he fell from power after confessing to the taking of bribes. He was dismissed from his high office and barred from Court. He said that he was "heartily sorry", but was ordered to pay a huge fine (later quashed by the king), and spent a brief time in the Tower of London.

xxxxxFrancis Bacon was a lawyer, essayist, statesman and philosopher, as well as a pioneer in scientific method. He was born in London, studied law at Trinity College, Cambridge, and became a Member of Parliament in 1584. Although a nephew of Lord Burleigh, he associated with his uncle's rival, the Earl of Essex, but turned against him when he led a revolt against Queen Elizabeth, and in 1601 helped to secure his conviction as a traitor. He defended this action in his Apology of 1604, in which he argued that his first loyalty was to his sovereign. He then went on to enjoy a successful legal career, ending up as Lord Chancellor in 1618. Three years later, however, he fell from power after confessing to the taking of bribes. He was dismissed from his high office and barred from Court. He said that he was "heartily sorry", but was ordered to pay a huge fine (later quashed by the king), and spent a brief time in the Tower of London.

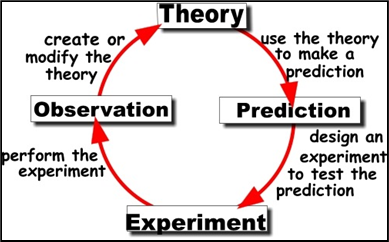

xxxxxIt was after this sudden turn of events that, denied access to the corridors of power, he turned to the study of science, a field in which he came to be regarded as the founder of modern scientific research. To his earlier treatise, The Advancement of Learning of 1605, he now added his New System (1620), and The New Atlantis, published in 1626. In these works he stressed the importance of scientific method and the need for a systematic programme of research based on experiment and observation in order that man might discover the simple laws governing the universe and use them to his own advantage. And it is in this approach to science that Bacon's philosophy can best be appreciated. Knowledge, he argued,

xxxxxIt was after this sudden turn of events that, denied access to the corridors of power, he turned to the study of science, a field in which he came to be regarded as the founder of modern scientific research. To his earlier treatise, The Advancement of Learning of 1605, he now added his New System (1620), and The New Atlantis, published in 1626. In these works he stressed the importance of scientific method and the need for a systematic programme of research based on experiment and observation in order that man might discover the simple laws governing the universe and use them to his own advantage. And it is in this approach to science that Bacon's philosophy can best be appreciated. Knowledge, he argued,  was the fruit of experience, and was not to be based on what he called "idols" -

was the fruit of experience, and was not to be based on what he called "idols" -

xxxxxBacon was also an accomplished writer. By 1597 he had completed his Essays, Civil and Moral, and these ten literary gems were revised and added to over the years and numbered 58 in the final edition of 1625. Couched in beautiful, eloquent prose, these take their place among the classics of English literature. He also wrote a history of the reign of Henry VII and a work entitled The Wisdom of the Ancients concerning the meaning of ancient myths. Butxthe idea, allegedly put forward by the English clergyman and scholar James Wilmot (1726-

xxxxxBacon was also an accomplished writer. By 1597 he had completed his Essays, Civil and Moral, and these ten literary gems were revised and added to over the years and numbered 58 in the final edition of 1625. Couched in beautiful, eloquent prose, these take their place among the classics of English literature. He also wrote a history of the reign of Henry VII and a work entitled The Wisdom of the Ancients concerning the meaning of ancient myths. Butxthe idea, allegedly put forward by the English clergyman and scholar James Wilmot (1726-

xxxxxHe was a Member of Parliament for thirty years and during this time produced a number of papers on statecraft. These included schemes for the union of England and Scotland, and proposals concerning the relationship between Crown and Commons, an issue then generating some heat. For his work as a statesman he was knighted in 1603, and became Baron Verulam in 1618 and Viscount St. Albans three years later. The English satirist Alexander Pope described Bacon as "the wisest, brightest and meanest of men". Like much of his comment, it was not far off the mark. Among those who held him in high esteem were the Englishmen Robert Boyle, Sir Isaac Newton, and Thomas Hobbes, and the French man-

xxxxxIncidentally, we are told that he died in the service of science. In March 1626, he suddenly stopped his carriage near Highgate, north London, and, buying a chicken, stuffed it with snow to see whether it would help to preserve it. During this impromptu experiment -

J1-