xxxxxThe English novelist Jane Austen is famous for her six novels, published (save for one) in the last seven years of her life: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Northanger Abbey, Mansfield Park, Emma and Persuasion. All provided a comedy of manners centred around the genteel life of a middle class community in rural England, and the plots were virtually the same: the entry of a young lady into society, seeking a suitable but happy marriage. But this study of ordinary country folk in their ordinary humdrum lives was made to come alive by Austen’s extraordinary ability to observe and describe in subtle, comic and often sardonic terms the characters that occupied her little world, and made up this privileged section of society. Far removed from the romantic melodrama then in vogue, these works may be seen as the forerunners of the “modern novel”. They were published anonymously, and although appreciated, especially by the Prince Regent and the Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott, they did not gain wide popularity until the 20th century. Pride and Prejudice, published in 1813, is her best known work.

JANE AUSTEN 1775 -

Acknowledgements

Austen: 1873, artist unknown, based on a drawing by her sister Cassandra c1810 – University of Texas Libraries, USA. Staël: by the French artist Élisabeth Vigée-

xxxxxJane Austen was one of England’s greatest fiction writers. Her six major works, produced in the last seven years of her life, played a significant role in the development of the English novel. Far removed from the romantic melodrama then in vogue, their realistic portrayal of ordinary people in ordinary situations made them the forerunners of the “modern novel”. Brilliantly constructed, keenly observed, and written in an elegant, witty and softly sardonic style, they all created, each in their different way, a fascinating comedy of manners, centred around the genteel, country life of middle-

xxxxxJane Austen was one of England’s greatest fiction writers. Her six major works, produced in the last seven years of her life, played a significant role in the development of the English novel. Far removed from the romantic melodrama then in vogue, their realistic portrayal of ordinary people in ordinary situations made them the forerunners of the “modern novel”. Brilliantly constructed, keenly observed, and written in an elegant, witty and softly sardonic style, they all created, each in their different way, a fascinating comedy of manners, centred around the genteel, country life of middle-

xxxxxShe was born in the small village of Steventon (near Basingstoke, Hampshire), where her father was the rector. The seventh of eight children, she attended school at Reading for a while, together with her elder sister Cassandra, but she received most of her education at home. She paid visits to friends and relatives, as well as the occasional trip to Bath or London, but, for the most part, the first twenty-

xxxxxWhen her father retired in 1801, the family moved to Bath -

xxxxxAusten began writing as a child, and her Love and Friendship, light and burlesque in style, was published when she was only 15 years old. While at Steventon she worked on three novels, though none was published until the last seven years of her life. All were alike in their comic portrayal of society and its members, and each used satire to make a particular point. Sense and Sensibility (then “Elinor and Marianne”) told the story of the two Dashwood sisters and their love affairs, and provided the means of poking fun at the current tendency to give vent to excessive emotion. Northanger Abbey (then “Susan”) was a skit on the current Gothic novel, with its emphasis on the sensational and macabre. Pride and Prejudice (then “First Impressions” and eventually published in 1813) centred around the attempts to find suitable husbands for the five Bennet sisters. This last work, perhaps the most popular of her novels, has as its heroine the attractive Elizabeth, a witty, strong-

xxxxxAusten began writing as a child, and her Love and Friendship, light and burlesque in style, was published when she was only 15 years old. While at Steventon she worked on three novels, though none was published until the last seven years of her life. All were alike in their comic portrayal of society and its members, and each used satire to make a particular point. Sense and Sensibility (then “Elinor and Marianne”) told the story of the two Dashwood sisters and their love affairs, and provided the means of poking fun at the current tendency to give vent to excessive emotion. Northanger Abbey (then “Susan”) was a skit on the current Gothic novel, with its emphasis on the sensational and macabre. Pride and Prejudice (then “First Impressions” and eventually published in 1813) centred around the attempts to find suitable husbands for the five Bennet sisters. This last work, perhaps the most popular of her novels, has as its heroine the attractive Elizabeth, a witty, strong-

xxxxxIt was after moving to Chawton in 1809 that she wrote here three later novels. Having published Sense and Sensibility at her own expense in 1811, she then produced in quick succession Mansfield Park (1814), Emma (1816), and Persuasion (published after her death). These, like her earlier works, were centred around the love affairs of their heroines, but their themes had a greater social awareness, highlighting the repressed and restricted nature of woman’s place in society. And developed in these works, too, was a deeper, almost psychological study of character. Mansfield Park, touching on religious duty, is her most serious work, whilst Emma is the lightest of the three.

xxxxxThe compass of her work was slight indeed, as were the plots themselves. Her novels were confined almost entirely to the amorous pursuits of young ladies, and the snobbery and social prejudices born of class distinction within a confined and privileged rural community. The Napoleonic Wars, then engulfing the continent, and the social unrest at home -

xxxxxThe compass of her work was slight indeed, as were the plots themselves. Her novels were confined almost entirely to the amorous pursuits of young ladies, and the snobbery and social prejudices born of class distinction within a confined and privileged rural community. The Napoleonic Wars, then engulfing the continent, and the social unrest at home -

xxxxxJane Austen’s novels were published anonymously, and though they were quite widely read, they did not prove particularly popular in her day, admired in the main by a small group which included the Prince Regent, the Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott, and the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey. It was not until the 20th century, in fact, that their worth came to be fully appreciated, both for their penetrating appraisal of a selected segment of English society, and for their brilliant creation of a host of realistic, often amusing, character studies. Early in 1817 she fell seriously ill -

xxxxxIncidentally, the novels Northanger Abbey and Persuasion contain amusing, tongue-

Including:

Madame de Staël and

Madame de Récamier

xxxxxAnother outstanding woman writer at this time was the French novelist and literary critic Madame de Staël (1766-

xxxxxAnother outstanding woman writer at this time was the French novelist and literary critic Madame de Staël (1766-

xxxxxAnne Louise Germaine Necker was born in Paris of Swiss parents. Her father, Jacques Necker, was the finance minister to the ill-

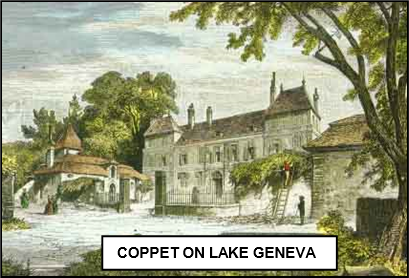

xxxxxShe returned to France in 1794, at the conclusion of the Reign of Terror, and gained her reputation as a writer in 1800 with the publication of The Influence of Literature upon Society, a work which championed the cause of women writers and comprehensively set out the theories of European Romanticism. Like the German writer Johann Gottfried Herder, she argued that morally and historically a work must be seen as the product of the nation in which it was conceived. By this time, however, her political essays, her open support for the English system of constitutional monarchy, and the liberal and radical ideas of her band of fellow intellectuals, had turned her into a dangerous political embarrassment. She became regarded as Napoleon’s most effective opponent in France, and the First Consul did not disagree. In 1803 he banned her from Paris, and it was from then that she began writing her “Ten Years’ Exile”, using her salon at Coppet as the intellectual centre from which to launch her attacks upon Napoleon’s arbitrary rule.

xxxxxShe returned to France in 1794, at the conclusion of the Reign of Terror, and gained her reputation as a writer in 1800 with the publication of The Influence of Literature upon Society, a work which championed the cause of women writers and comprehensively set out the theories of European Romanticism. Like the German writer Johann Gottfried Herder, she argued that morally and historically a work must be seen as the product of the nation in which it was conceived. By this time, however, her political essays, her open support for the English system of constitutional monarchy, and the liberal and radical ideas of her band of fellow intellectuals, had turned her into a dangerous political embarrassment. She became regarded as Napoleon’s most effective opponent in France, and the First Consul did not disagree. In 1803 he banned her from Paris, and it was from then that she began writing her “Ten Years’ Exile”, using her salon at Coppet as the intellectual centre from which to launch her attacks upon Napoleon’s arbitrary rule.

xxxxxIt was in the early years of this period of exile that she travelled through Germany and accumulated the material for her most important literary work. Entitled On Germany and published in 1810, this was a critical study of German culture, noted particularly for its appraisal of the romantic movement known as Sturm und Drang. Such was her esteem for all things German, that Napoleon regarded the work as a sleight against the French and banned its publication in France, destroying some 10,000 copies! In the meantime, she also published her two semi-

xxxxxShe returned to Paris following the restoration of the monarchy, but found the city occupied by foreign troops and saw little or no prospect of a liberal form of government emerging. She travelled in Italy for a short while and then returned to Coppet in the summer of 1816. Here she was joined by Lord Byron -

xxxxxShe returned to Paris following the restoration of the monarchy, but found the city occupied by foreign troops and saw little or no prospect of a liberal form of government emerging. She travelled in Italy for a short while and then returned to Coppet in the summer of 1816. Here she was joined by Lord Byron -

xxxxxA woman of immense intellect and wide ranging interest, she wrote plays, novels, political tracts and numerous critiques. Her writings included Letters on the Works and the Character of J.-

xxxxxIncidentally, Staël had numerous love affairs, including a long, passionate relationship with the Swiss novelist and political writer Benjamin Constant (1767-

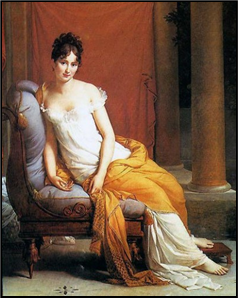

xxxxx…… Thexportrait (above) of Madame de Staël is by the fashionable French artist Élisabeth Vigée-

xxxxxAnother successful hostess in France at this time was Madame de Récamier (1777-

xxxxxAnother successful hostess in France at this time was Madame de Récamier (1777-

xxxxxAnother woman writer at this time was the French novelist and literary critic Madame de Staël (1766-

G3c-