xxxxxAs we have seen, the Italian Sebastian Cabot was one of the first navigators to explore Argentina in 1526. The Spanish soldier Pedro de Mendoza followed ten years later, making the first settlement at Buenos Aires, and soon after this Spanish colonists began arriving from the Pacific coast. By the end of the century ten or more cities had been established. In 1776 Buenos Aires became the capital of the viceroyalty of La Plata, an area also covering Uruguay, Paraguay and southern Bolivia. The opportunity to gain independence came in 1810 with the overthrow of the Spanish king, Ferdinand VII, by Napoleon. A junta was formed in the name of the deposed king, but it had little popular support. An independence movement, led by Manuel Belgrano and José de San Martin, quickly gathered strength, and won independence for Argentina in July 1816. After many years of turmoil a federal government was established, but it was not until 1862 that the province of Buenos Aires took its place in the federation.

ARGENTINA GAINS ITS INDEPENDENCE

1810 -

Acknowledgements

Map (La Plata): from

history.howstuffworks.com. Belgrano:

detail, by the French artist François Casimir Carbonnier (1787-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Italian

Sebastian Cabot was one of the first navigators to explore Argentina. In 1526,

employed by the Spanish, he sailed up the Parana and Paraguay

rivers, but when his promises of finding silver came to nothing,

the Spanish crown showed no interest in the area. Ten years later

a settlement was established at Buenos Aires by the Spanish

soldier Pedro de Mendoza, but after five years this was abandoned

because of constant Indian attacks. Soon after this, however,

Spanish colonists began crossing into Argentina from the Pacific

coast, and by the end of the century ten or more cities had been

established, including Santa Fe in 1573. Also among this number

was Buenos Aires, resettled in 1580. Because of its commanding

position as an east-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Italian

Sebastian Cabot was one of the first navigators to explore Argentina. In 1526,

employed by the Spanish, he sailed up the Parana and Paraguay

rivers, but when his promises of finding silver came to nothing,

the Spanish crown showed no interest in the area. Ten years later

a settlement was established at Buenos Aires by the Spanish

soldier Pedro de Mendoza, but after five years this was abandoned

because of constant Indian attacks. Soon after this, however,

Spanish colonists began crossing into Argentina from the Pacific

coast, and by the end of the century ten or more cities had been

established, including Santa Fe in 1573. Also among this number

was Buenos Aires, resettled in 1580. Because of its commanding

position as an east-

xxxxxIronically enough, it was in that year, 1776, that the American colonies declared their independence and went on to win it from Britain. Then came the French Revolution and the successful fight for freedom in the French colony of Saint Domingue (Haiti), led by Toussaint Louverture in 1791. Such events would not have gone unnoticed in Argentina or, indeed, the other colonial lands in South America. But it was the coming of the Napoleonic Wars which marked the turning point. In 1806 the British navy attacked and occupied Buenos Aires but, after a short time, was ably expelled by the local militia, as was an expeditionary force sent the following year. This did a great deal to bolster the confidence of the colonists and awake their patriotic spirit.

xxxxxBut it was the overthrow of the Spanish king,

Ferdinand VII, a year later -

xxxxxBut it was the overthrow of the Spanish king,

Ferdinand VII, a year later -

xxxxxAs is often

the case, the declaration of independence was followed by a bitter

struggle for power between those who favoured a centralised form

of government, based on Buenos Aires, and those seeking a federal

constitution. The next ten years in particular saw a complete

break down of law and order, made the worse by a war with Brazil

in 1825 to 1827, successful though it proved to be. Thexfederalists eventually won but, in the meantime, the

country had to endure seventeen years of dictatorship (1835-

Including:

Independence Movements

in Paraguay and Chile,

Bernado O’Higgins and

José de San Martin

xxxxxBut when Argentina

began its fight for independence in 1810, the other members of the

Viceroy of La Plata -

xxxxxBut when Argentina

began its fight for independence in 1810, the other members of the

Viceroy of La Plata -

xxxxxAs we have seen, in 1776

Paraguay become part of the Viceroyalty of La Plata. This

arrangement, imposed by Spain, alarmed the colony’s leaders, who

resented the growing importance of Buenos Aires, and feared that

they would be swallowed up by their larger neighbour. Thus when

Argentina began its fight for independence in 1810, Paraguay refused

to be part of it. This appeared to seal the colony’s fate, but when

the Argentine general Manuel Belgrano launched an invasion the

following year, his forces were repulsed by a people determined to

save their “nation”. Then in May of that year, led by two leaders of

the militia, Pedro Juan Cabellero and Fulgencio Yegros, they deposed

the governor and declared their own independence. BuenosxAires then sent an envoy to Asuncion to threaten or

bribe the colony into submission, but a new strong man, José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia

(1766-

xxxxxWhen Argentina gained its independence in 1816, the other members of the Viceroy of La Plata would have none of it. They wanted freedom on their own terms. Paraguay was the first to go its own way. The colony had been founded by one of Mendoza’s lieutenants in the early 1540s after travelling 1000 miles up the Plata and Paraguay rivers. He established Asuncion as the centre of the colony of Paraguay. In 1776 it was administered by Buenos Aires, but when the fight for independence began in 1810, Paraguay refused to be part of it. The Argentine general Belgrano led an invasion, but this was repulsed and in October 1813 a new strong man, Jose Gaspar Rodriguez de Francia declared Paraguay’s independence. He ruled the country as a dictator until 1840, and similar despots then followed, one of whom, as we shall see, was to provoke a war with no less than three of his neighbours in 1865 (Vb).

G3c-

xxxxxThe

Spanish soldier Diego de Almagro, a one-

xxxxxItxwas in 1535

that the Spanish soldier Diego de Almagro

(c1475-

xxxxxItxwas in 1535

that the Spanish soldier Diego de Almagro

(c1475-

xxxxxHowever, by the 1560s much of the country had been subdued under the governorship of Don Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza, and Spanish settlers began to arrive, though never in large numbers. Because there was little mineral wealth, society was very largely based on agriculture, and this attracted little interest in Spain itself. By the end of the colonial period the population, which numbered around 500,000, was mostly made up of Mestizos (mixed Indian and European) and Creoles (Chilean born Spaniards), with only 20,000 pure Spaniards (known as “peninsulares”).

xxxxxAlthough

the colony lived a somewhat isolated existence, it was influenced,

like the other colonial lands, by freedom struggles overseas. As in

Argentina, its fight for independence began in 1810, triggered off

by events in Spain. In that year the Creoles

formed a junta in Santiago aimed at self-

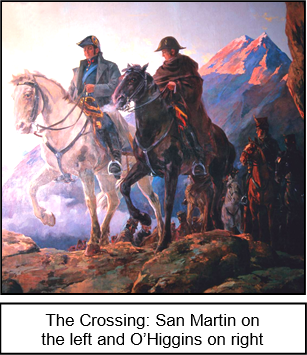

xxxxxInxthe city of Mendoza,

however, he joined up with the revolutionary leader José

de San Martin. Afterxtwo

years planning the invasion, their combined forces, some 5,000

strong, crossed into Chile -

xxxxxInxthe city of Mendoza,

however, he joined up with the revolutionary leader José

de San Martin. Afterxtwo

years planning the invasion, their combined forces, some 5,000

strong, crossed into Chile -

xxxxxO’Higgins

was made supreme director of Chile in 1817, having seen off a

challenge from his rival Carrera, and in 1818 proclaimed the

country’s independence -

xxxxxAfter

the Battle of Chacabuco, José de San Martin was offered the

leadership of the new, independent Chile, but he declined in favour

of O’Higgins. As we shall see (1824 G4), San Martin was anxious to organise a sea invasion of

Peru, Spain’s strongest and richest possession on the continent. And

also bent on gaining freedom for that country was the so called

Latin American “Liberator” Simon  Bolivar,

a man who, apart from Peru, was to play an important part in the

independent movements in Columbia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia.

Bolivar,

a man who, apart from Peru, was to play an important part in the

independent movements in Columbia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia.

xxxxxIncidentally, the crossing of the Andes in January 1817 by José de

San Martin and his army -