THE HUNDRED YEARS’ WAR 1339 -

THE BATTLE OF AGINCOURT 1415 (H5)

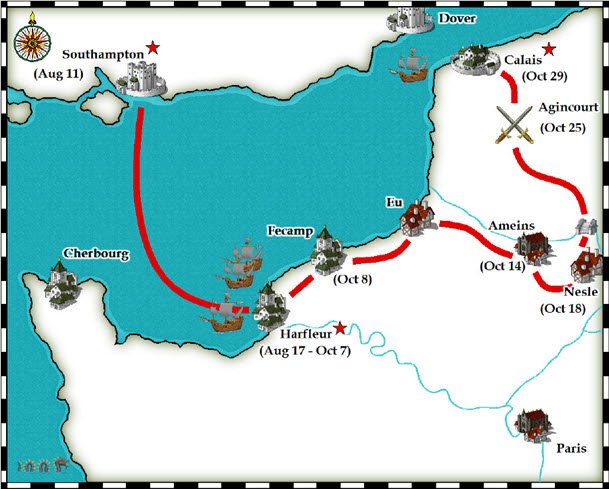

xxxxxHenry V, laying claim to the French throne and with an army of some 10,000 men, took the port of Harfleur in the summer of 1415, and then marched north towards Calais. The journey proved a disaster through lack of food and widespread sickness, so that when Henry was confronted with a large French force at Agincourt, south of Calais, he attempted to come to terms. But the French would not hear of it, and battle was joined. Although out-

xxxxxHenry V set sail for France in August 1415 and landed near the port of Harfleur in Normandy with a well-

xxxxxHenry V set sail for France in August 1415 and landed near the port of Harfleur in Normandy with a well-

xxxxxThe battle commenced on the morning of St. Crispin’s Day. The English drew up in four ranks, their archers in the front and protected against cavalry by a line of stakes driven into the ground. Heavily outnumbered though they were - overnight rain had made the ground wet and soggy, favouring the lightly armoured English troops. Thus when the heavily armoured French cavalry opened the attack, they floundered in the mud, were held up by the wall of stakes, and proved an easy target for the English archers. Struck down by an almost continuous hail of arrows, their ranks broke up in panic. And, likewise, when the armoured French infantry attacked, those that survived the volleys of the dreaded longbow proved no match for the lightly equipped, mobile English foot soldiers wielding short swords and axes. The first line of the attack was quickly overwhelmed, and then the English infantry advanced and, in hand-

overnight rain had made the ground wet and soggy, favouring the lightly armoured English troops. Thus when the heavily armoured French cavalry opened the attack, they floundered in the mud, were held up by the wall of stakes, and proved an easy target for the English archers. Struck down by an almost continuous hail of arrows, their ranks broke up in panic. And, likewise, when the armoured French infantry attacked, those that survived the volleys of the dreaded longbow proved no match for the lightly equipped, mobile English foot soldiers wielding short swords and axes. The first line of the attack was quickly overwhelmed, and then the English infantry advanced and, in hand-

xxxxxThis English victory, one of the most significant battles in the Hundred Years’ War, made a deep psychological impression upon the French. They lost over 6,000 men, including their leader, Charles d’Albret and 1,500 knights, whilst the English casualties numbered no more than 1,600. WhenxHenry returned to the continent in 1417 there was no repeat of such a notable triumph, but by a series of sieges he took over the towns and fortresses of Normandy and, with the eventual fall of Rouen in 1419 and the threat this posed to Paris, the French quickly came to terms by the Treaty of Troyes in 1420.

xxxxxBy this treaty Henry was recognised as the Regent of France and successor to the deranged Charles VI, an agreement made the more positive by his marriage to the king’s young daughter Catherine. But the Dauphin, it must be noted, the rightful heir to the French throne, took no part in the treaty, and Henry had to continue the fight. With Henry’s unexpected death in 1422, the future changed direction. The map shows the land held by England at the end of the reign but, as we shall see, in 1429 (H6) the Hundred Years’ War took a marked turn in favour of the French.

xxxxxIncidentally, Saint Crispin has no significance as far as fighting or battles are concerned. There were two saints, in fact, Saint Crispin and Saint Crispinian (illustrated). Legend has it that they were brothers born of a noble Roman family in the 3rd Century who, as Christians, feared persecution. They fled to Soissons in France (then Suessiona in Gaul) where they converted many people to Christianity. As they supported themselves by making shoes, they have come to be regarded as the saints of shoemakers. The emperor at that time, Maximian, had t hem beheaded, and a number of places claim to house their remains. A Kentish tradition has it that their bodies were thrown into the sea and were washed up at Romney Marsh! Agincourt’s connection with Saint Crispin is simply because Shakespeare, in his play Henry V, noted that the battle was fought on the saint’s feast day, the 25th October.

hem beheaded, and a number of places claim to house their remains. A Kentish tradition has it that their bodies were thrown into the sea and were washed up at Romney Marsh! Agincourt’s connection with Saint Crispin is simply because Shakespeare, in his play Henry V, noted that the battle was fought on the saint’s feast day, the 25th October.

H5-

Acknowledgements

Map (France); by courtesy of Mark Needham, www.timeref, Medieval Maps. Agincourt: contemporary illustration from St. Alban’s Chronicle (1376-