xxxxxAs we have seen, the First Anglo-Afghan War was an unmitigated disaster for the British. In 1839 (Va), concerned about the growing influence of Russia in the area, they invaded Afghanistan in order to gain control of the country. They quickly took over the major cities, but their harsh rule was opposed by many tribesmen, and in November 1841 a revolt broke out in Kabul. British officials were murdered and a military detachment of 300 men was lost. Eventually the garrison was granted safe conduct to India, but on its journey to the frontier 4,500 troops and 12,000 civilians were attacked and massacred. Later that year the British invaded Afghanistan again and took revenge on Kabul, but they lacked the strength to stay in control of the country and were forced to return to India.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the First Anglo-Afghan War was an unmitigated disaster for the British. In 1839 (Va), concerned about the growing influence of Russia in the area, they invaded Afghanistan in order to gain control of the country. They quickly took over the major cities, but their harsh rule was opposed by many tribesmen, and in November 1841 a revolt broke out in Kabul. British officials were murdered and a military detachment of 300 men was lost. Eventually the garrison was granted safe conduct to India, but on its journey to the frontier 4,500 troops and 12,000 civilians were attacked and massacred. Later that year the British invaded Afghanistan again and took revenge on Kabul, but they lacked the strength to stay in control of the country and were forced to return to India.

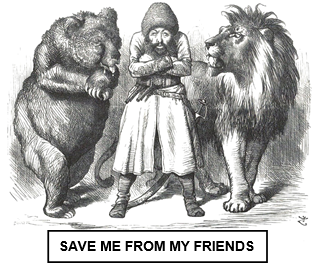

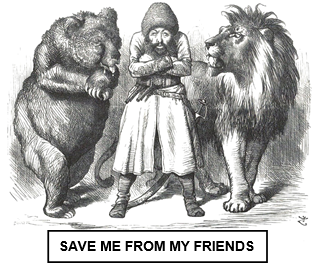

xxxxxIn the thirty years that followed this war the Russians continued to advance slowly but surely towards Afghanistan, an advance regarded as a threat to British India by hard-line conservatives. By 1865 Tashkent had been taken over and three years later the Russians were in Samarkand. Then a peace treaty in that year with Amir Muxaffar al-Din, the ruler of Bukhara, brought Russian control as far as the River Amu Darya, along the northern border of Afghanistan. Matters came to a head in July 1878. As we have seen, in that month the Congress of Berlin had settled the international dispute between Britain and Russia by modifying the terms of the Treaty of San Stefano, an agreement which, imposed upon Turkey at the end of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 , had given the Russians virtual control over the Balkans. Its ambitions thwarted in that area, a somewhat humiliated Russia now turned its attention to Central Asia. Towards the end of July it sent a diplomatic mission to Kabul in order to increase its influence in Afghanistan and pose a threat to British India.

xxxxxIn the thirty years that followed this war the Russians continued to advance slowly but surely towards Afghanistan, an advance regarded as a threat to British India by hard-line conservatives. By 1865 Tashkent had been taken over and three years later the Russians were in Samarkand. Then a peace treaty in that year with Amir Muxaffar al-Din, the ruler of Bukhara, brought Russian control as far as the River Amu Darya, along the northern border of Afghanistan. Matters came to a head in July 1878. As we have seen, in that month the Congress of Berlin had settled the international dispute between Britain and Russia by modifying the terms of the Treaty of San Stefano, an agreement which, imposed upon Turkey at the end of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 , had given the Russians virtual control over the Balkans. Its ambitions thwarted in that area, a somewhat humiliated Russia now turned its attention to Central Asia. Towards the end of July it sent a diplomatic mission to Kabul in order to increase its influence in Afghanistan and pose a threat to British India.

xxxxxThis mission, it would seem, had not, in fact, been invited by the emir, Shere Ali Khan, but viewed from London, it was seen by the British as a friendly act towards the Russians. As a result in August they demanded that a British mission be likewise established at Kabul. When no reply was received - the Afghan court was in mourning at that time following the death of the Emir’s son and heir - the British despatched an envoy to Kabul, accompanied by a small military detachment. However, on reaching the Khyber Pass this mission was refused entry to Afghanistan. As far as the British were concerned this “insult” provided a convenient pretext for a full-scale invasion. The Second Anglo-Afghan War was under way.

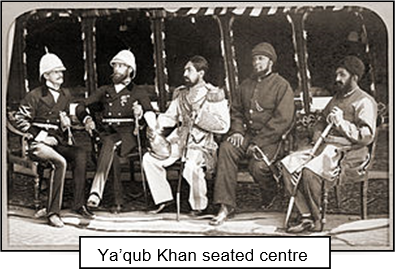

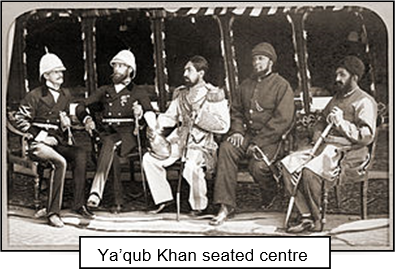

xxxxxIn the first phase of the war, beginning in November, Anglo-Indian forces numbering around 35,000 men, invaded the country at three points. Shere Ali Khan sought help from Russia, but when none was forthcoming, he fled from his capital and took refuge in Turkestan. He died there in February 1879. Byxthat time the British had won the Battles of Ali Masjid and Peiwar Kotal, captured Kabul, and occupied much of the country. As a result the new emir, Ya’qub Khan, son of Shere Ali Khan, was forced to come to terms. Byxthe Treaty of Gandamak, signed in May (illustrated), he was recognised as the rightful emir, and his country was provided with an annual subsidy. In return, however, Ya’quib agreed to conduct his foreign affairs in accordance with the “wishes and advice” of the British government, and permitted the establishment of a British embassy in Kabul. In addition the Khyber and Michni passes were ceded to Britain.

xxxxxBut the war was by no means over. At the beginning of September 1879 the newly established British envoy in Kabul, Sir Louis Cavagnari, was murdered, along with his military escort, and the second phase of the war began. Anglo-Indian forces had once again to cross the mountain passes into Afghanistan. Afterxwinning the Battle of Charasia, they occupied Kabul before the end of October and, mindful of the rebellion which had occurred during the first war, brutally crushed any signs of dissension. Ya’qub was forced to abdicate, and was sent into exile in India.

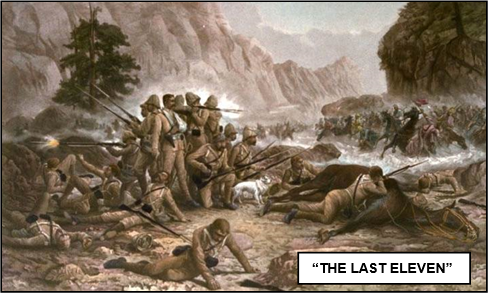

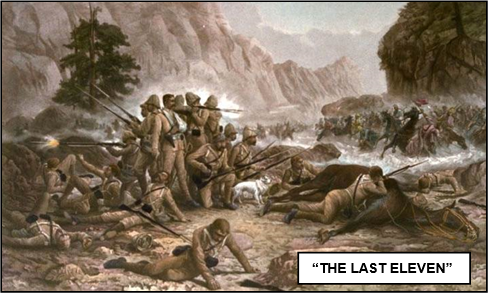

xxxxxInx1880, however, the Afghans mounted a Holy War (a Jihad) to drive the infidel out of their country. At the Battle of Maiwand (illustrated), in July of that year, the heavily outnumbered British were totally defeated by a large army of regular and irregular troops led by Ayub Khan, a son of Shere Ali Khan and ruler of Herat Province in the north-west. Those who managed to escape the carnage struggled to Kandahar where the garrison was soon under siege. Inxresponse, a rescue column some 10,000 strong, led by General Sir Frederick Roberts (1832-1914), set out from Kabul and, after an historic forced march of 320 miles, relieved the city on the last day of August. Thexfollowing day the Ayub Khan’s army was routed at the decisive Battle of Kandahar, and this marked the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

xxxxxInx1880, however, the Afghans mounted a Holy War (a Jihad) to drive the infidel out of their country. At the Battle of Maiwand (illustrated), in July of that year, the heavily outnumbered British were totally defeated by a large army of regular and irregular troops led by Ayub Khan, a son of Shere Ali Khan and ruler of Herat Province in the north-west. Those who managed to escape the carnage struggled to Kandahar where the garrison was soon under siege. Inxresponse, a rescue column some 10,000 strong, led by General Sir Frederick Roberts (1832-1914), set out from Kabul and, after an historic forced march of 320 miles, relieved the city on the last day of August. Thexfollowing day the Ayub Khan’s army was routed at the decisive Battle of Kandahar, and this marked the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

xxxxxThe invasion force eventually withdrew from Afghanistan in April 1881. If nothing else the British had learnt that battles might be won, but permanent control of the country as a colonial possession was not a feasible proposition. However, before they left they put a pro-British emir on the throne - Abd-ar-Rahman, nephew of Shere Ali Khan - and this ensured that the country’s foreign affairs remained in British hands. And this continued to be the case until 1919 when the Third Anglo-Afghan War - a series of skirmishes led by Abd ar-Rahman’s grandson, Amanullah Shah - put an end to British involvement in the affairs of Afghanistan … for the time being.

xxxxxIncidentally, the forced march from Kabul to Kandahar in August 1880 has gone down in military history as a feat of human endurance and organisation. The rescue mission, lasting some 20 days, was carried out in temperatures of 100 degrees Fahrenheit and over dry, rugged terrain. A medal was struck for those who took part in the operation, and the man who led the march, General Sir Frederick Roberts (known affectionately as “Bobs” by his troops) later took the title Lord Roberts of Kabul and Kandahar, and was commander-in-chief during the Second Anglo-Boer War of 1899 (Vc). ……

xxxxx…… The statue known as the Maiwand Lion was erected in Forbury Gardens, in the town of Reading, Berkshire, England, in 1886 in memory of the 328 men of the 66th Berkshire Regiment who were killed in the battle. ……

xxxxx…… The Indian-born British writer Rudyard Kipling composed a poem about the Anglo-Afghan wars entitled The Young British Soldier. The last verse gives this telling advice to any soldier who is left wounded on the battlefield:

When you’re wounded and left on Afghanistan’s plains,

And the women come out to cut up what remains,

Jest roll to your rifle and blow out your brains,

An’ go to your Gawd like a soldier.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the First Anglo-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the First Anglo- xxxxxIn the thirty years that followed this war the Russians continued to advance slowly but surely towards Afghanistan, an advance regarded as a threat to British India by hard-

xxxxxIn the thirty years that followed this war the Russians continued to advance slowly but surely towards Afghanistan, an advance regarded as a threat to British India by hard-

xxxxxInx1880, however, the Afghans mounted a Holy War (a Jihad) to drive the infidel out of their country. At the Battle of Maiwand (illustrated), in July of that year, the heavily outnumbered British were totally defeated by a large army of regular and irregular troops led by Ayub Khan, a son of Shere Ali Khan and ruler of Herat Province in the north-

xxxxxInx1880, however, the Afghans mounted a Holy War (a Jihad) to drive the infidel out of their country. At the Battle of Maiwand (illustrated), in July of that year, the heavily outnumbered British were totally defeated by a large army of regular and irregular troops led by Ayub Khan, a son of Shere Ali Khan and ruler of Herat Province in the north-