xxxxxAfter

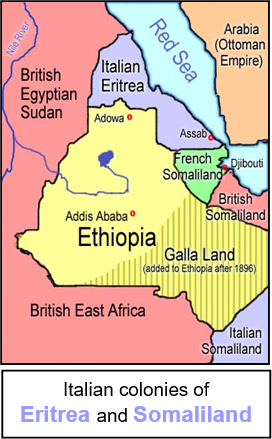

occupying Eritrea and Somaliland in north-

THE FIRST ITALO-

THE BATTLE OF ADOWA 1896 (Vc)

Acknowledgements

Map (Horn of Africa): licensed under Creative Commons – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlas_of_Ethiopia. Baratieri: date and artist unknown. Battle of Adowa: date and artist unknown – British Museum, London. Victory: illustration (subsequently coloured) from a French newspaper, 1896, artist unknown. Map (Eritrea): considered to be in the public domain – https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eritrea. Map (Eastern Africa): from www.courses.wcupa.edu/jones/his312/maps. Mussolini: date and artist unknown. Menelik II: date and artist unknown – British Museum, London.

xxxxxBecause their country was not unified until 1861, the

Italians were late joining in the scramble for Africa. It had its

beginning in 1869 when an Italian shipping company bought the

rights of Assab Bay on the West coast of the Red Sea. The Italian

government, having failed, as we have seen, to acquire the North

African state of Tunisia in

1881, bought

out these rights the following year, and by 1890 had officially

established the colony of Eritrea, its first possession on the

African continent. Fairly small in size by African standards, but

holding an important strategic position near the entry to the Red

Sea, this territory was bordered by the Sudan in the west, Ethiopia in the south, and the French colony of Somaliland in the south-

xxxxxBecause their country was not unified until 1861, the

Italians were late joining in the scramble for Africa. It had its

beginning in 1869 when an Italian shipping company bought the

rights of Assab Bay on the West coast of the Red Sea. The Italian

government, having failed, as we have seen, to acquire the North

African state of Tunisia in

1881, bought

out these rights the following year, and by 1890 had officially

established the colony of Eritrea, its first possession on the

African continent. Fairly small in size by African standards, but

holding an important strategic position near the entry to the Red

Sea, this territory was bordered by the Sudan in the west, Ethiopia in the south, and the French colony of Somaliland in the south-

xxxxxIt

was around this time that the Italians sought to extend further

their territory in this remote north-

xxxxxGiven that he was taking on a powerful European nation,

this was indeed a brave decision. However, because of the very real

threat to the country’s independence, he succeeded in winning over

the vast majority of his feudal nobles, and this enabled him to

field a much larger army than the Italians expected. Putting his

trust in God -

xxxxxGiven that he was taking on a powerful European nation,

this was indeed a brave decision. However, because of the very real

threat to the country’s independence, he succeeded in winning over

the vast majority of his feudal nobles, and this enabled him to

field a much larger army than the Italians expected. Putting his

trust in God -

xxxxxBaratieri took the first step. He moved a column forward to occupy the town of Adigrat and, having put to flight an enemy attack, surged forward to occupy the mountain fortress of Amba Alage. In military terms this appeared to be an impregnable position, but wave after wave of Ethiopians then attacked up the steep slopes, and after six hours and heavy loses the summit was reached and the fortress overran. Only 400 men of the garrison of 2,000 managed to escape. The commander Major Toselli was killed in the battle, and was likened by the Italians to the British soldier General Gordon of Khartoum, a white hero who had died in the service of his country in the heart of the Dark Continent. Worse was to follow. Those who escaped fled to Mekelle and this town was quickly besieged by a large Ethiopian force in January 1896. The town’s water supply was cut off and, only after Baratieri had agreed to renegotiate all aspects of the conflict, was the garrison allowed to withdraw. But the following month the “negotiations” as far as the Italians were concerned was simply a demand that the emperor accept the Treaty of Wuchale and this, as they knew, would not be acceptable.

xxxxxBy

the end of the month both armies were once again drawn up around the

town of Adowa. By this time, however, both sides were quickly

running out of food supplies. The Italians were on half rations, and

the huge Ethiopian army was having to live off the land and little

was left for its survival. Reluctantly Menelik decided he needed to

sta rt

disbanding his force on the 2nd March. Unfortunately for Baratieri

(as it turned out), goaded by his government to take action in order

to avenge the defeats at Amba Alage and Mekelle, he chose the 1st of

March 1896 for his all-

rt

disbanding his force on the 2nd March. Unfortunately for Baratieri

(as it turned out), goaded by his government to take action in order

to avenge the defeats at Amba Alage and Mekelle, he chose the 1st of

March 1896 for his all-

xxxxxHis plan was to keep one column in reserve, and to send the three others, commanded by Generals Albertone, Arimondi and Dabormida, to take up the heights overlooking the Ethiopian forces. The advance was made during the night of the 29th February, and this proved the downfall of the campaign. Because of the rugged nature of the terrain and the lack of accurate maps, all three columns lost their way and their contact with each other.

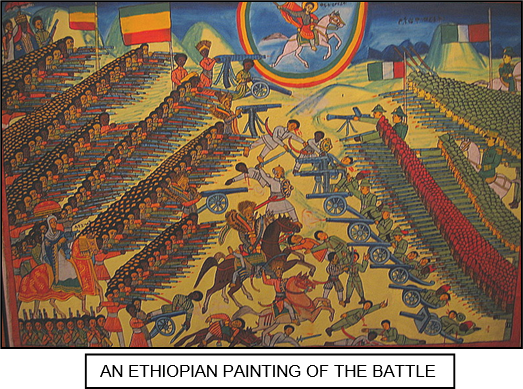

xxxxxAt first light Albertone made a wrong turn and marched his men

directly towards the Ethiopians, encamped at the base of Mount Enda

Chdane Meret. For three hours they were bombarded and charged

repeatedly by Ethiopian warriors. Then Menelik committed his 25,000

imperial guard to the battle, and the Italian troops were overrun

and put to flight. Meanwhile on the right flank the column led by

General Dabormida had become separated from the remainder of the

Italian forces and in making a dash for the fortified position of

Sauria was caught in the narrow valley of Mariam Shavitu. With

little space to manoeuvre the Italians were slaughtered almost to a

man by the Orono cavalry, a tribe noted for their horsemanship and

ferocity. The centre columns with the reserve forces commanded by

Baratieri, fared no better. They were outflanked on the slopes of

Mount Bellah and destroyed piecemeal by a much larger enemy force

attacking from the front and both flanks.

xxxxxAt first light Albertone made a wrong turn and marched his men

directly towards the Ethiopians, encamped at the base of Mount Enda

Chdane Meret. For three hours they were bombarded and charged

repeatedly by Ethiopian warriors. Then Menelik committed his 25,000

imperial guard to the battle, and the Italian troops were overrun

and put to flight. Meanwhile on the right flank the column led by

General Dabormida had become separated from the remainder of the

Italian forces and in making a dash for the fortified position of

Sauria was caught in the narrow valley of Mariam Shavitu. With

little space to manoeuvre the Italians were slaughtered almost to a

man by the Orono cavalry, a tribe noted for their horsemanship and

ferocity. The centre columns with the reserve forces commanded by

Baratieri, fared no better. They were outflanked on the slopes of

Mount Bellah and destroyed piecemeal by a much larger enemy force

attacking from the front and both flanks.

xxxxxBy

noon all those who had survived the onslaught were in full retreat.

Close to half the Italian army were killed or wounded during the

battle. Those who were captured were forced marched to Addis Ababa

and repatriated on the payment of a large indemnity by the Italian

government, put at ten million lira. Left on the various fields of

battle were all the Italian artillery -

xxxxxForxthe Italians the battle of Adowa was a complete and humiliating defeat, and it produced violent and widespread protest throughout Italy. At the Treaty of Addis Ababa in the October the Italian government was obliged to accept unconditionally the sovereignty and independence of Ethiopia. This, it seems, is all that Menelik wanted. He might well have gained more, but he chose not to carry the war further by driving the Italians out of their colony of Eritrea. A number of reasons have been put forward for that decision. His troops were battle weary, supplies were running low, there was a serious lack of horses, and fresh Italian troops were on their way. But above all, he realised that for the Italian people the loss of Eritrea would turn a colonial debacle into a national crusade, and then his country’s independence would certainly be lost.

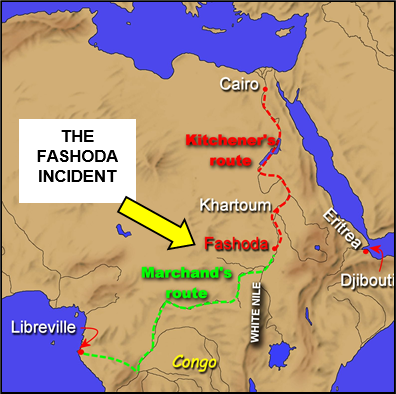

xxxxxAs it

was, the triumph of the Ethiopians - lf.

For long they had harboured the idea of joining their colonial

possessions together from the Atlantic to the Red Sea, and the

control of southern Sudan -

lf.

For long they had harboured the idea of joining their colonial

possessions together from the Atlantic to the Red Sea, and the

control of southern Sudan -

xxxxxIncidentally, the Battle of Adowa was the major encounter in the

First Italo-

xxxxxIncidentally, the Battle of Adowa was the major encounter in the

First Italo-

xxxxx…… At the end of the war in 1896 a small number of Italian prisoners were tortured, and some 800 Eritrean askaris had their right hands and left feet cut off, the punishment meted out to traitors. Many of these died from their wounds. ……

xxxxx…… Russia’sxinterest

in this part of Africa had its beginnings in 1889 when a Russian

soldier of fortune named Nikolai

Ivanovich Achinov (b.1856), with the

half-

xxxxxMenelikxII

(1844-

Vc-

Including:

Menelik II