xxxxxAs we have seen, the Second Anglo-Dutch War, breaking out in 1664, had ended in humiliation for the English. In 1667 the Dutch had sailed up the Thames and destroyed Chatham dockyard and a large amount of shipping. In 1670 Charles II, anxious to avenge this defeat, made a secret treaty with Louis XIV of France against the Protestant Republic. In 1672 and 1673, however, both their fleets were repulsed by the Dutch, and the following year Charles made a separate treaty with the Republic and brought the Third Anglo-Dutch War to an end. Meanwhile the Franco-Dutch War continued. The French, who had designs on the Spanish Netherlands, and wanted the Dutch suitably subdued, had invaded and occupied a large part of the Dutch Republic by 1673. In that year, however, the Holy Roman Emperor and the Elector of Brandenburg gave their support to the Dutch, and the French were driven back to their own border. Undeterred, Louis XIV continued the fight, and by the Treaties of Nijmegen in 1678 and 1679 France was ceded frontier land from the Spanish, including a part of Burgundy, Artois and 16 fortified towns in Flanders. These gains were valuable to the French, but the war had proved a costly affair.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Second Anglo-Dutch War, breaking out following the English capture of New Amsterdam in 1664, ended three years later on a loud note of humiliation for England. In the wake of two major disasters, the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London the following year, the Dutch had set fire to the port of Sheerness and, sailing up the Thames and Medway, had destroyed Chatham dockyard and a large part of the fleet that was moored there.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Second Anglo-Dutch War, breaking out following the English capture of New Amsterdam in 1664, ended three years later on a loud note of humiliation for England. In the wake of two major disasters, the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London the following year, the Dutch had set fire to the port of Sheerness and, sailing up the Thames and Medway, had destroyed Chatham dockyard and a large part of the fleet that was moored there.

xxxxxAgainst such a background, further conflict between the two naval powers was inevitable, and it was not long in coming. Both Charles II, a Roman Catholic at heart, and his cousin, Louis XIV of France, shared a dislike of the Dutch Protestant Republicans. Charles was anxious to avenge the humiliating defeat suffered at their hands in 1667 and, at the same time, reduce their maritime strength in the struggle for world trade. For his part, Louis XIV was determined to subdue the Dutch by one means or another in order to have a free hand in his designs on the Spanish Netherlands. By what later came to be known as the Secret Treaty of Dover of May 1670, both kings agreed to an offensive alliance against the Dutch, the English receiving a generous subsidy for their promise of support.

xxxxxThus the Third Anglo-Dutch war was part of a wider conflict between France and the United Provinces of the Netherlands, known as the Franco-Dutch War. In May 1672 the French, supported by the English navy, invaded the Dutch Republic and within a short time had occupied three of the seven provinces. They would clearly have advanced further had not the Dutch, under their commander  William of Orange (the future king of Great Britain), opened the dikes around Amsterdam and flooded a large area of their country. This stopped the French in their tracks, and gave the Dutch valuable time to rebuild their depleted and ill-trained army.

William of Orange (the future king of Great Britain), opened the dikes around Amsterdam and flooded a large area of their country. This stopped the French in their tracks, and gave the Dutch valuable time to rebuild their depleted and ill-trained army.

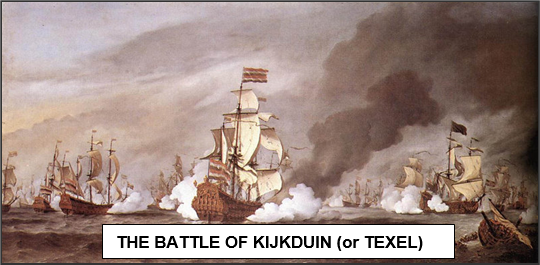

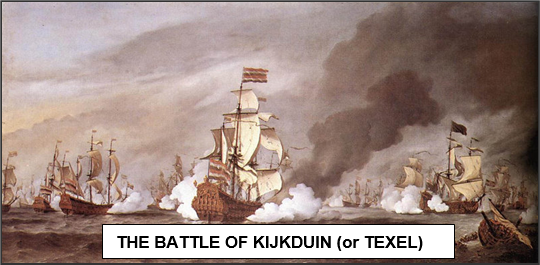

xxxxxMeanwhile, at sea, the Dutch Admiral de Ruyter repulsed attacks by both English and French fleets in battles off Solebay in 1672 and off Ostend and Kijkduin the following year. Such was the stalwart defence put up by the Dutch navy, that the allies failed to blockade the Dutch coast or to land troops ashore. Unablexto make headway, and fully aware of the mounting opposition at home to a war against the protestant Dutch, Charles negotiated a separate peace by the Treaty of Westminster in February 1674. By it, the pre-war situation was virtually restored, the Dutch retaining Surinam but returning New Amsterdam.

xxxxxFor Louis XIV, the war continued. In 1673 Spain, the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold I, and the Elector of Brandenburg had entered the war on the side of the Dutch, and by the end of the year the alliance had driven the French out of the Republic. But the French were successful in their main objective - the strengthening of their eastern border. Over the next four years, aided by the Swedes, they advanced steadily into the Spanish Netherlands and along the Rhine, the forces of the Grand Alliance offering no serious resistance. Butxthe long war proved costly and Louis XIV eventually decided to make peace. The Treaties of Nijmegen, 1678 and 1679, left the Dutch Republic damaged but intact, but from the Spanish the French gained Franche-Comté (in Burgundy), Artois, and 16 fortified towns in Flanders. Such frontier gains made the fighting worthwhile.

xxxxxIncidentally, the painting above - depicting the Battle of Kijkduin (also known as the Battle of Texel) - was by the Dutch marine artist Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633-1707). He came to England in 1673 and worked for Charles II, the Duke of York, and various members of the nobility for many years. His rendering of the sea is particularly realistic, whether in calm or stormy conditions, and his detailed portrayal of the ships, particularly their rigging, has proved historically valuable. There is a collection of his works in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (including The Gust and The Cannon Shot, shown here), and a number of his paintings are in the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection in London. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, the painting above - depicting the Battle of Kijkduin (also known as the Battle of Texel) - was by the Dutch marine artist Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633-1707). He came to England in 1673 and worked for Charles II, the Duke of York, and various members of the nobility for many years. His rendering of the sea is particularly realistic, whether in calm or stormy conditions, and his detailed portrayal of the ships, particularly their rigging, has proved historically valuable. There is a collection of his works in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (including The Gust and The Cannon Shot, shown here), and a number of his paintings are in the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection in London. ……

xxxxx…… It was during this third Anglo-Dutch encounter that the Dutch launched a surprise attack upon New York. They recaptured the city (formerly New Amsterdam) from the English, and changed its name yet again, this time to New Orange in honour of their commander William III, Prince of Orange! By the Treaty of Westminster the following year, however, the city was returned to the English and its name was restored. To complete the picture, the city eventually came to be known as “The Big Apple”, the name of a popular dance which was all the rage in the jazz quarter of Manhattan during the 1930s and 1940s!

xxxxx…… It was during this third Anglo-Dutch encounter that the Dutch launched a surprise attack upon New York. They recaptured the city (formerly New Amsterdam) from the English, and changed its name yet again, this time to New Orange in honour of their commander William III, Prince of Orange! By the Treaty of Westminster the following year, however, the city was returned to the English and its name was restored. To complete the picture, the city eventually came to be known as “The Big Apple”, the name of a popular dance which was all the rage in the jazz quarter of Manhattan during the 1930s and 1940s!

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Second Anglo-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Second Anglo- William of Orange (the future king of Great Britain), opened the dikes around Amsterdam and flooded a large area of their country. This stopped the French in their tracks, and gave the Dutch valuable time to rebuild their depleted and ill-

William of Orange (the future king of Great Britain), opened the dikes around Amsterdam and flooded a large area of their country. This stopped the French in their tracks, and gave the Dutch valuable time to rebuild their depleted and ill-

xxxxxIncidentally, the painting above -

xxxxxIncidentally, the painting above - xxxxx…… It was during this third Anglo-

xxxxx…… It was during this third Anglo-